As educators and school leaders return to campus after two years of significant upheaval and loss, many are prioritizing efforts focused on students’ well-being, including ensuring that students receive adequate mental health support. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, some experts suggest that the stressors associated with the pandemic and learning from home may have impacted students’ mental health, potentially increasing students’ risks of self-harm and suicide.1 Given this increased concern about student mental health, many school districts have recently and rapidly adopted self-harm monitoring systems.

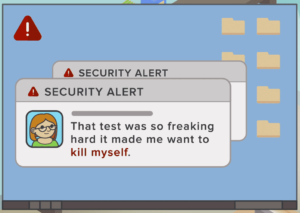

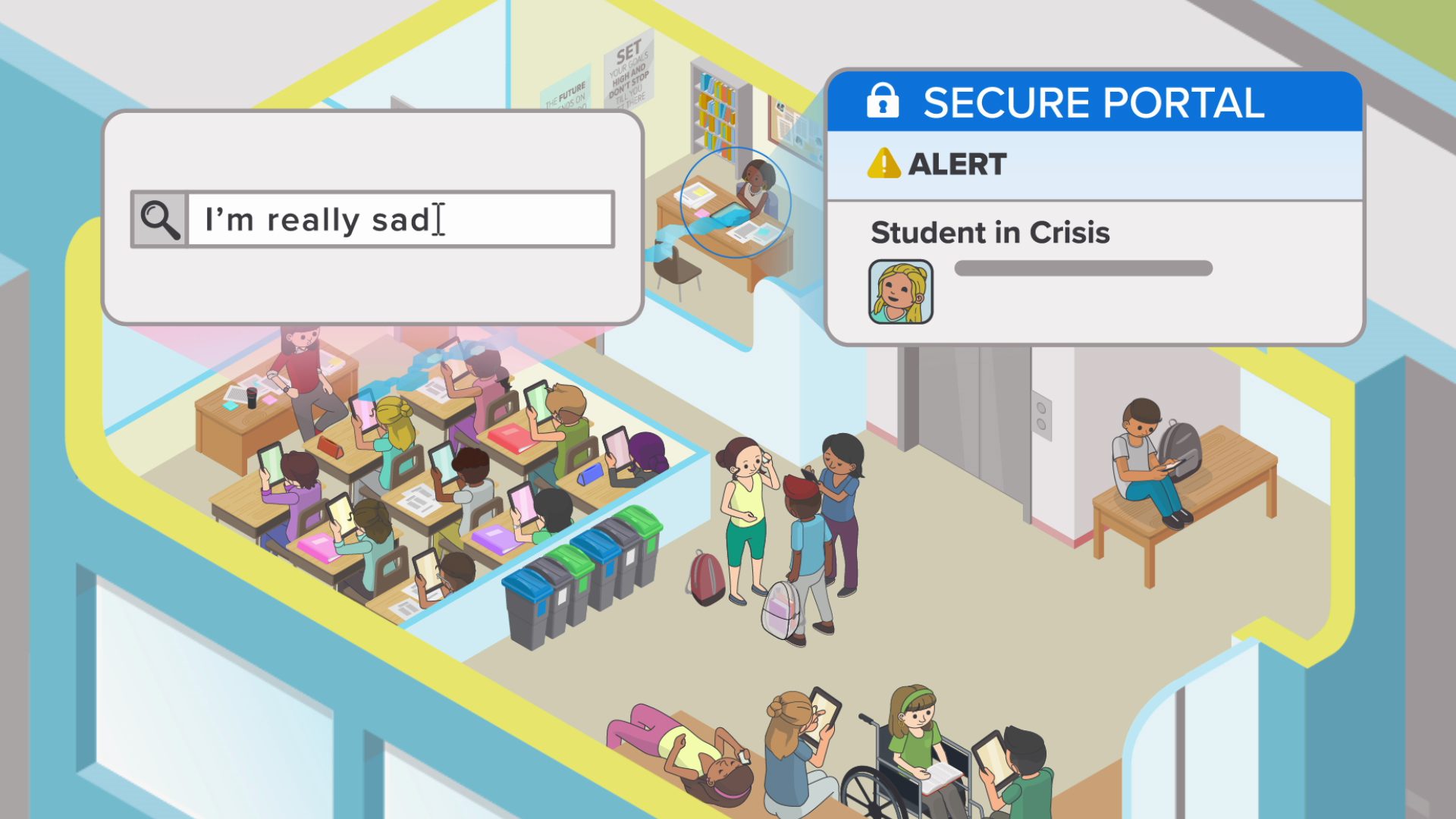

Self-harm monitoring systems are computerized programs that can monitor students’ online activity on school-issued devices, school networks, and school accounts to identify whether students are at risk of dangerous mental health crises. These monitoring systems identify individual students by processing and collecting personal information from their online activities and sending alerts about individual students and their flagged content to school officials. In some cases, these systems or school policies facilitate sharing this information with parents or third parties, such as law enforcement agencies.

Despite their increased use, self-harm monitoring systems are an unproven technique for effectively identifying and assisting students who may be considering self-harm simply based on their online activities.

School districts may overestimate the ability of self-harm monitoring systems to identify students and underestimate the importance of developing comprehensive policies and processes for using the systems. Due to the inherent limitations in a computer system’s ability to interpret context, these systems often inaccurately or mistakenly flag student content and over-collect confidential data.2

The increased and rapid adoption of these systems raises important questions about the effectiveness and consequences of self-harm monitoring systems for students’ mental health, privacy, and equity. Monitoring systems can scan and monitor students’ searches, emails, documents, and online activities including social media and online communications on school-issued devices. Education leaders must carefully weigh the risks and harms associated with adopting monitoring technologies, implement safeguards and processes to protect students who may be identified, establish a strong communications strategy that includes school staff, students, parents,3 and caregivers, and ensure that their schools’ and districts’ monitoring programs and service-delivery systems do not exacerbate inequities. Further, schools must have the necessary mental health resources and professionals (school-based psychologists, counselors, and social workers) in place to support students identified by the program, which most schools across the country do not have.4

Merely adopting monitoring systems cannot serve as a substitute for robust mental health supports provided in school or a comprehensive self-harm prevention strategy rooted in well-developed medical evidence. Identifying students alone does not equate to supporting their mental health.

Absent other support, simply identifying students who may be at risk of self-harm—if the system does so correctly—will, at best, lead to no results. At worst, it can violate a student’s privacy or lead to a misinformed or otherwise inappropriate response. Schools must have robust mental health response plans in place to effectively support any students who may be identified before adopting monitoring systems.

Without proper planning and recognition of monitoring systems’ limitations, using monitoring software as a self-harm detection tool can trigger unintended consequences. In particular, using self-harm monitoring systems without strong guardrails and privacy-protective policies is likely to disproportionately harm already vulnerable student groups. Potential harmful outcomes include:

- Students being mistakenly flagged,

- Students being unfairly treated once flagged as a result of improper sharing of this status and bias or stigma around mental illness,

- Students being subject to excess scrutiny by the school in ways that can be stigmatizing and alienating,

- Students having mental health details or their status-as-flagged inappropriately disclosed,

- Students being needlessly put in contact with law enforcement and social services, or facing school disciplinary consequences as a result of being flagged,

- Students having sensitive personal information, such as gender identity, sexual orientation, citizenship status, religious beliefs, political affiliations, or family situation revealed or shared, and

- Students experiencing a chilling effect, making them hesitant to search for needed resources on school devices out of fear of being watched by school officials or flagged by the monitoring system.

All of these outcomes could ultimately undermine the primary goal of improving students’ mental well-being.5 To mitigate this, schools must:

- Ensure they have sufficient school-based mental health resources and appropriate processes in place to support any students with mental health needs if they are accurately identified through self-harm monitoring technology,

- Develop a robust mental health response plan beyond simply identifying students through a monitoring system, and

- Have well-developed policies governing how schools will use monitoring systems, respond to alerts, and protect student information before they acquire the technology.

To help education leaders understand and weigh these risks, this report describes self-harm monitoring technology and how schools use it, details the privacy and equity concerns introduced by these monitoring systems, points out challenges that undermine the accuracy and limit the usefulness of these systems for addressing student mental health crises, outlines legal considerations related to monitoring students for self-harm, provides crucial questions that school and district leaders should consider regarding monitoring technologies, and offers recommendations and resources to help schools and districts protect students’ privacy in the context of monitoring for self-harm.

Background: What Is Self-Harm Monitoring Technology and How Do Schools Use It?

Schools often adopt self-harm monitoring technology with the best intentions: to help keep students safe and improve their well-being. However, if implemented without due consideration to the significant privacy and equity risks posed to students, these programs may harm the very students that need the most support or protection, while ineffectively fulfilling their intended purpose of preventing self-harm.

Before adopting self-harm monitoring technology, schools and districts should understand the risks self-harm monitoring technology can pose to students’ privacy and safety, take thoughtful steps to mitigate those risks, and carefully weigh the risks against any benefits.6 After weighing the equities, some schools choose not to adopt this technology. When schools choose to adopt, strong privacy and equity practices must be identified and implemented.

Why do schools use monitoring technology?

Schools generally use monitoring software with two goals: legal compliance and to keep students safe.

Legal Compliance

Most schools adopted monitoring software long before self-harm monitoring software was available in order to comply with the Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA). When CIPA was enacted more than 20 years ago, the role of software was to block access to obscene or harmful content, and monitoring typically took place in a computer lab, where teachers and school staff could view, in person, the content students were accessing on their school computers. Today, schools across the country provide students with various options to learn through technology, including requiring students to bring their own devices to school7 or providing them with school-issued laptops, tablets,8 or mobile hotspots,9 dramatically increasing the breadth and invasiveness of monitoring that can occur. The type and extent of monitoring required by the law has been interpreted unevenly by different districts, ranging from fairly minimal approaches to much more extensive interpretations.10 The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has yet to publish guidance on CIPA and monitoring. In addition to the lack of guidance on CIPA’s practical application, there is also no guidance on how CIPA interacts with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), a federal education privacy law that grants parents and students specific rights to student education records (go here for more on FERPA’s application to student monitoring).

Remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Box 3 discussing the effect of the pandemic) has only increased student usage and reliance on school-mediated technology, especially take-home internet hotspot devices issued by schools to help close the digital divide. In response to the pandemic, in August 2021, the FCC announced more than $5 billion in school and library-issued requests to fund 9.1 million connected devices, with 5.4 million broadband connections through the Commission’s Emergency Connectivity Fund.11 Without clarity on CIPA’s requirements, schools may unintentionally over-surveil and over-collect sensitive, personal information about students or their families in an attempt to comply with the law. For example, monitoring on school-issued hotspot devices brought home by students may not be limited solely to school hours, and may capture internet activities of not just the student but also other members of the household.

In addition to CIPA, schools may be subject to state-level filtering and cyberbullying laws that may require them to implement filtering and monitoring technology to ensure that students safely access the internet for school purposes.

Keeping Students Safe

In addition to legal obligations, schools want to ensure the wellbeing of their students. The internet has enabled access to inappropriate content, bullying in cyberspace in addition to school hallways, and sharing of inappropriate images. The rapid adoption by schools of communication and collaboration tools from Google and Microsoft, driven in part recently by remote learning needs,12 has also generated large volumes of student communications and digital content. Because of these factors, monitoring technologies are often appealing to many schools, families, and other education stakeholders who seek to know what students are doing online,13 including identifying when students are facing mental health concerns and particularly when students are looking up information about self-harm or suicide.

Many policymakers and educators hope that these monitoring systems can help schools identify students at risk of self-harm or suicide so that schools can direct them to help and resources they might not otherwise receive. For example, in early 2021, a Florida legislator sought funding for schools across the state to adopt the monitoring provider Gaggle to “protect Florida youth from suicide and self-harm.”14 Similarly, the North Carolina Coronavirus Relief Act 3.0 made $1 million “available to public school units to purchase one or more Gaggle safety management products to enhance student safety while providing remote instruction.”15 Local education leaders also see a need to adopt self-harm monitoring systems. In 2019, for example, a school system in Wilson County, Tennessee expanded its monitoring system, designed initially to detect violent threats to school safety, to also scan student-created content on school devices, such as emails and online posts, for signs of self-harm. A counselor in the school district described the monitoring system as generating red flags in response to keywords, including “self-harm,” “suicide,” and “overdosing,” or phrases such as “I just want to cut myself.”16 Importantly, the district noted that the program was incorporated in a larger process—when such online activity is identified as a potential source of harm, counselors can then perform a risk assessment, involve parents, and offer mental health resources. In the first two months of 2019, Wilson County schools told News4 Nashville that they had identified 11 cases requiring intervention using their expanded monitoring system, although these cases were not limited to suicide-related comments and also included language related to drug use and sharing inappropriate photos.

Self-harm monitoring companies and the media have shared similar accounts and experiences from other school districts as well. In Caddo Parish Public Schools in Louisiana, the district’s instructional technologist reported that the self-harm monitoring system Lightspeed Alert helped identify a student contemplating suicide during the pandemic.17 In Las Vegas, a 12-year-old student was flagged by his school after he used his school-issued iPad to search for “how to make a noose.”18 Neosho School District in Missouri told NPR that the district has identified a struggling student at least once per semester, which enables them to conduct an early intervention.19 These anecdotes illustrate just a few of the compelling reasons why schools and districts may want to adopt self-harm monitoring technologies.

Charged with the care of children, schools have clear incentives to look for straightforward indicators of self-harm risks; they would certainly want to catch students messaging classmates with a plain intention to harm themselves, or students querying a search engine for ways to die by suicide. But those circumstances—in which there is a clear, imminent danger of a student about to harm themselves—are fortunately rare, and scanning for self-harm using monitoring systems often seeks to identify situations that are much more ambiguous.

What do schools monitor?

Monitoring technologies generally work by scanning and flagging (marking for action by the system based on certain criteria) students’ online activities and content on school-issued devices, school networks, and certain school services (e.g. Google Workspace or Microsoft Office 365) for indications that a student may be at risk of harming themselves.

As discussed above, CIPA specifically requires schools that receive federal E-Rate funding to filter and monitor20 students’ online activity to prevent them from accessing inappropriate content, such as graphic, violent, or sexually explicit material.21 When schools adopt self-harm monitoring software, it often is an addition to this more general monitoring occurring in the district.

Each type of monitoring software is different, and may offer different features. Generally, monitoring software is either scanning all web traffic—the information received and sent in a web browser (such as Chrome, Firefox Safari, or Edge)—or monitoring the content of specific applications owned by the school, such as their email (such as Outlook or Gmail), file storage (such as Microsoft OneDrive or Google Drive), and school-managed chat applications (such as Google Chat or Microsoft Teams). Several monitoring software companies also provide an option for classroom management software, which allows a teacher to monitor the screens and web browsing of their students during a class session, and focus the class’s attention by preventing web browsing, pushing a web page to all students, or focusing student’s attention on a specific web page. Unlike general internet filtering software (which may filter or monitor student’s personal devices that connect to a school network or a school-provided wireless hotspot), self-harm monitoring software is typically installed only on school-provided devices. However, when there is monitoring of certain school-managed services (e.g. Google Workspace or Microsoft Office 365), monitoring can occur on both school-provided and personal devices since the monitoring software is scanning all content created in those accounts.

How does monitoring occur?

When monitoring software is scanning web traffic or specific applications, it could either 1) scan the content and only keep content when it is “flagged” as inappropriate or otherwise problematic,22 or 2) keep all of the content that is scanned so schools officials can retrospectively see the websites that specific students were visiting and some of their activities online.

This process of reviewing, “flagging,” and alerting will be familiar to anyone that has ever received an alert from their credit card company of a suspicious transaction. While some schools deploy technology that simply emails an administrator when a student accesses an inappropriate website, email or search term,23 other schools use more intensive monitoring that creates a log of each student’s search and web browsing activity.24

Monitoring services overwhelmingly employ algorithms that scan and detect key words or phrases across different platforms.25 These algorithms can be based on simple natural language processing of keywords or may attempt to use other types of artificial intelligence26 to examine the context of the content to improve the reliability of the “flagging” process.27 Some monitoring services go beyond algorithms and employ a second step in their flagging process, in which the content is reviewed by respective monitoring companies’ internal personnel to check for false positives or to review additional context to better understand the flagged content.28

The alerting process varies between services and in different situations. For many monitoring services, different content can trigger different alerts or responses. For example, terms or activity that monitoring services have grouped into lower-level or less serious inappropriate content may simply be blocked.29 If more serious inappropriate content is flagged or detected, students may receive warnings by email for violations, and school administrators may be copied in instances of multiple warnings.30 When content indicating a possible threat to a student’s personal safety or the safety of other students is detected, it could result in direct personal notification to the school or, in extreme cases, to law enforcement or emergency services.31 These more extensive monitoring services can allow school officials to see what each student has been doing online (and, with some software, can automatically send that information to parents).32

How common is student monitoring in schools?

Monitoring technology has become prevalent in schools throughout the country. E-rate funding is provided to approximately 95 percent of schools,33 so most schools have some web filtering and monitoring system that blocks access to content that is obscene or harmful to minors in order to comply with CIPA. In recent nationwide research with teachers whose schools use monitoring systems, 52 percent reported their school’s monitoring included flagging keyword searches such as “Information on self-harm monitoring.”34 For example, more than 15,000 schools use the monitoring service Securly, and 10,000 schools use the service GoGuardian.35 However, all of these services only advertise their number of subscribers for their general CIPA monitoring or classroom management services, and not for their specific self-harm monitoring service. As a result, it is unclear what percentage of their subscribing schools have chosen to use self-harm monitoring detection in addition to their existing monitoring services. In contrast, Gaggle, which is used in over 1,500 school districts,36 does not provide CIPA content filtering directly and focuses exclusively on self-harm, violence, and objectionable content monitoring.

How is self-harm monitoring different from monitoring generally?

Self-harm monitoring systems present a new, significant turn from the way schools have used monitoring systems for content filtering and CIPA compliance over the past 20 years. By seeking to draw conclusions about students’ mental health status based on their online activities and initiating actions involving school officials and other third parties based on these inferences, self-harm monitoring systems introduce greater privacy risks and unintended consequences for students.

Several online monitoring companies that market to schools have expanded their services to offer monitoring technology that specifically seeks to identify students at risk of self-harm or suicide. These services employ the same general flagging and alerting process described above, but with a specific focus on content that might implicate suicide or other forms of self-harm. A range of content may be flagged, and the appropriate response or alert may depend on the severity of the content, such as whether intentions of self-harm appear with evidence of an imminent plan.37 For example, the monitoring company Lightspeed has a product called “Alert”, which employs “safety specialists”38 who escalate immediately “to district safety personnel and/or law enforcement, enabling early intervention”39 if a student’s plan to harm themselves is deemed imminent. The monitoring company GoGuardian offers the alert service “Beacon,” which scans browser traffic to and from “search engines, social media, emails, chats, apps, and more” for “concerning activity surrounding self-harm and suicide.”40 Managed Methods, a student online monitoring service, offers a “Student Self-Harm Detection” tool that is described as detecting “self-harm content in school Google Workspace and Microsoft 365 apps.”41 Securly Auditor and Gaggle similarly monitor content in school Google Workspace and Microsoft 365 apps. While not the primary focus of this report, a relatively small number of schools have also used dedicated tools that scan students’ social media posts for indicators of self harm or other threats.42

More extensive monitoring services can allow school officials to see what each student has been doing online.

Concerns and Challenges Associated with Monitoring Technologies: Important Considerations for School Districts

Schools often adopt self-harm monitoring technology with the best intentions: to help keep students safe. However, if implemented without due consideration of the significant privacy and equity risks posed to students, these programs can harm the very students that need the most support or protection, while ineffectively fulfilling their intended purpose of preventing self-harm.

While monitoring companies claim to have flagged thousands of instances of self-harm content, there is no information available about how many of the students that were identified in these examples were found to be truly at-risk of self-harm as diagnosed by a mental health professional, how many students in these districts were at-risk but not picked up by the system, and what the context and size of the student population are in these publicized cases. No independent research or evidence43 has established that these monitoring systems can accurately identify students experiencing suicidal ideation, considering self-harm, or experiencing mental health crises.44 Self-harm monitoring technologies remain unproven as a prevention strategy and have not been substantiated by mental health professionals and clinicians as an effective tool for addressing mental health crises.

It is difficult to conclude the effectiveness and benefit of self-harm monitoring systems based solely on a few anecdotal examples shared by school districts and monitoring companies, especially when there are countervailing anecdotes of false flags and invasions of privacy. For example, The 74 reported in 2021 that the monitoring software Gaggle, used in Minneapolis Public Schools, “flagged the keywords ‘feel depressed’ in a document titled ‘SEL Journal,’ a reference to social-emotional learning” taught as part of the school curriculum. In another instance, it “flagged the term ‘suicidal’ in a student’s document titled ‘mental health problems workbook.’”45 Gaggle’s CEO shared that a student “wrote in a digital journal that she suffered with self esteem issues and guilt after getting raped,” which allowed school officials to “‘get this girl help for things that she couldn’t have dealt with on her own.’” The Guardian reported in 2019 that school officials had received “red flags when students tell each other sarcastically to ‘kill yourself’, talk about the band Suicide Boys, or have to write a school assignment on the classic American novel To Kill a Mockingbird.”46 Education Week reported that in Evergreen Public Schools in Washington State, at least a dozen students were flagged by monitoring software when they “stored or sent files containing the word ‘gay.’”47 These incidents demonstrate how monitoring systems can both flag innocuous, extraneous content and create significant privacy incursions of sensitive student information. These privacy incursions and the related legal concerns for the districts running monitoring software (described here) can be exacerbated when the majority of content flagged occurs when students are at home outside of normal school hours.48

Simultaneously, deploying self-harm monitoring technology raises important privacy and equity considerations that education leaders must consider. Schools and districts that consider or use self-harm technology must therefore weigh the harmful implications of using this technology against the uncertainty of its benefits or effectiveness. The section below outlines these specific privacy and equity considerations.

Privacy and Equity Concerns Raised by Self-Harm Monitoring Technology

Before adopting self-harm monitoring technology, schools and districts should understand the risks self-harm monitoring technology can pose to students’ privacy and safety and carefully weigh those risks against any benefits.

Schools have widely and rapidly adopted self-harm monitoring technologies, despite the fact that they are relatively new and unstudied.49 Over the past two years, adoption increased as concerns grew about students struggling with mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.50 These facts raise important questions about the privacy risks and implications of monitoring that schools must carefully consider prior to implementation and revisit regularly. Such privacy risks may lead to disproportionate harms to students who are identified by self-harm monitoring, with especially inequitable consequences for systemically neglected groups of students. Suicide and self-harm disproportionally affect these vulnerable student populations, such as certain students who are minoritized in terms of race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability status, or experiencing homelessness.51 Moreover, students who are identified as “at-risk” may feel they have a target on their backs, with their personal struggles given limited privacy in school.

When schools use monitoring software, students deserve clear policies around what data is collected, who has access to it, how it will be used, and after what period it will be destroyed. Students deserve the assurance that all collected data will not be misused and that data collection and storage will be privacy-protective. Students deserve to have their schools held accountable, with clear consequences for those who put student privacy at risk by violating data sharing protocols. And students, educators, and families all deserve transparency.

The following privacy, equity, and implementation considerations guide the analysis in the following section. School leaders should ask themselves these key questions as they consider implementing a self-harm monitoring system:

- How will the school district create a school-wide mental health support program that is equitable and inclusive, and how does the technology fit into that program?

- Does the school district employ staff (e.g. school psychologists, school counselors, and school social workers) with expertise to address mental health concerns that may be detected?

- What kinds of information do monitoring systems identify and flag, is the system collecting more information than the purpose requires, and how long will the data be retained?

- What harms, such as stigma or discrimination, may stem from collecting and/or sharing students’ information or flagged status?

- Who has access to the information identified or flagged, and do they have a legitimate health or educational purpose for accessing it?

- How is student information shared with third parties, if at all, and are such disclosures permitted by law?

- How does the school district plan to provide transparent communication with families and students about monitoring policies, and how have they ensured that monitoring plans meet community needs?

How will the school district create a school-wide mental health support program that is equitable and inclusive, and how does the technology fit into that program?

Merely adopting monitoring systems cannot serve as a substitute for robust mental health supports provided in school or a comprehensive self-harm prevention strategy rooted in well-developed medical evidence. Schools must have robust mental health response plans in place to effectively support any students who may be identified before adopting monitoring systems.

Schools and districts should carefully consider and discuss the extent to which self-harm monitoring is necessary and beneficial to the goals of their mental health support program, and, if so, craft evidence-based policies to manage the privacy and equity risks. These goals need to be clearly stated and specific in their scope. Goals such as “improving student mental health,” or “saving lives” are too general because the connection between the tool and the steps required to achieve the goal are not evident. Specific goals define the problems to be solved and provide benchmarks to measure how successfully the chosen tool addresses the problem. Schools should have a clear explanation for why self-harm monitoring is necessary, as opposed to, for example, establishing deeper systems of school-based mental healthcare and providing more robust preventative care resources to students. If the benefit of adopting self-harm monitoring technology will not outweigh the privacy and equity risks, and if there are other ways to fulfill the goals of the mental health support program, schools and districts should reconsider monitoring altogether.

If monitoring technology is adopted, it must be implemented as just one component of the broader mental health response plan. Identifying students alone does not support students or give them access to help. Monitoring companies agree that effective self-harm monitoring cannot solely rely on software and must be part of a comprehensive mental health approach by schools.52 Absent other support, simply identifying students who may be at risk of self-harm—if the system does so correctly—will, at best, lead to no results. At worst, it can violate a student’s privacy or lead to a misinformed or otherwise inappropriate response.

Does the school district employ staff (e.g. school psychologists, school counselors, and school social workers) with mental health expertise to address concerns that may be detected through self-harm monitoring systems?

It is imperative that schools employ professionals with the expertise (e.g. school psychologists, school counselors, and school social workers) necessary to identify and address mental health concerns such as depression and anxiety. Unlike these professionals, teachers and school administrators are typically not licensed to identify and address mental health concerns and crises.  In the absence of staff with this specialized knowledge and training, mental health misconceptions can drive and negatively influence even the best-intentioned efforts to help students. The American Civil Liberties Union found in 2019 that millions of students nationwide attend schools with no counselors, no school nurses, no school psychologists, and no school social workers.53 Lack of personnel and in-school support means that flagging students via monitoring does not necessarily lead to help and resources for the students when there are none available in the school for them to receive. Likewise, simply informing a student’s parents that their child has been flagged by a school monitoring system as at-risk for self-harm will not necessarily result in the student receiving appropriate mental health supports—many parents may be left unsure what to do with this information, especially in the absence of in-school or community-based resources and services that they can access.

In the absence of staff with this specialized knowledge and training, mental health misconceptions can drive and negatively influence even the best-intentioned efforts to help students. The American Civil Liberties Union found in 2019 that millions of students nationwide attend schools with no counselors, no school nurses, no school psychologists, and no school social workers.53 Lack of personnel and in-school support means that flagging students via monitoring does not necessarily lead to help and resources for the students when there are none available in the school for them to receive. Likewise, simply informing a student’s parents that their child has been flagged by a school monitoring system as at-risk for self-harm will not necessarily result in the student receiving appropriate mental health supports—many parents may be left unsure what to do with this information, especially in the absence of in-school or community-based resources and services that they can access.

What kinds of information do monitoring systems identify and flag, is the system collecting more information than the purpose requires, and how long will the data be retained?

Identifying content indicating a student’s intent to self-harm is more challenging than it may seem. The data and activities that each monitoring system flags vary. A system may flag a student’s activity when their content matches specific words or phrases, based on an algorithm or a machine learning model.54 As a result, monitoring systems often fail to capture context or correctly interpret colloquial language that many students use. Peer-reviewed empirical research has repeatedly shown that context is extraordinarily difficult for most computer programs to accurately interpret,55 such that monitoring systems end up simply searching for certain words and flagging them without the capacity to determine what they mean and how they are being used. A computer program is therefore prone to interpret many innocuous phrases as dangerous language and raise alerts, thereby flagging content unrelated to any mental health condition or any intent to self-harm.56

For example, the search history of a student conducting research on the poet Sylvia Plath or grunge-rock legend Kurt Cobain—both of whom died by suicide—might look remarkably similar to the searches of a student suffering from depression.  Similarly, students who share innocuous posts using slang about a “photobomb” or how their parents are “killing them” may be mistakenly flagged for using terms associated with violence.57 This is an inherent shortcoming of using monitoring technology as a self-harm reduction strategy; it can penalize students for conducting research or expressing and exploring their feelings in developmentally normal ways. Published research studies58 on the subject suggest that monitoring and flagging student content in this way can have a chilling effect59 on students’ healthy and natural exploration while making students hesitant to seek help when they need it.60

Similarly, students who share innocuous posts using slang about a “photobomb” or how their parents are “killing them” may be mistakenly flagged for using terms associated with violence.57 This is an inherent shortcoming of using monitoring technology as a self-harm reduction strategy; it can penalize students for conducting research or expressing and exploring their feelings in developmentally normal ways. Published research studies58 on the subject suggest that monitoring and flagging student content in this way can have a chilling effect59 on students’ healthy and natural exploration while making students hesitant to seek help when they need it.60

While some monitoring systems may include a broad range of default categories and indicators out of a well-intentioned belief that it is best to capture any and all alarming student content possible, flagging overbroad keywords can reduce a monitoring program’s potential effectiveness. In systems with a more narrow self harm focus, school officials may be able to adjust alert settings to monitor categories such as profanity. Including such overbroad indicators increases the administrative burden on school officials and provides little benefit, inundating them with vast amounts of normal student content that require extensive staff time and effort to review. This makes it harder for school staff to notice and identify flagged content actually related to risk of self-harm, and detracts time and resources from providing useful follow-up for any true risks and student needs.

Moreover, some monitoring systems flag data and activities by default that are unrelated to self-harm but that the school district or monitoring company may consider otherwise inappropriate or concerning. For example, Buzzfeed reported in 2019 that one monitoring company included “LGBTQ-related words like ‘gay,’ ‘lesbian,’ and ‘queer’” as keywords that sent alerts to school officials (under the category of keywords that were monitored “in the context of possible bullying and harassment”).61 Other monitoring companies have filtered and blocked access to websites related to health resources for LGBTQ teens, news outlets that cover LGBTQ issues, anti-discrimination advocacy pages, and professional associations for LGBTQ individuals as part of their general monitoring regimen.62 These flags and blocks risk inadvertently disclosing a student’s gender identity or sexual orientation. This disproportionate flagging of LGBTQ students by monitoring systems can expose them to the privacy harms associated with monitoring and can even directly endanger their safety by exposing their sexual orientation or gender identity to school officials, families, or third parties. For more on the unique harms LGBTQ students may face as a result of monitoring technology in schools, and the legal implications of disparate flagging, see Legal Implications and Boxes 1 and 2.

Finally, a key factor in limiting unnecessary over-collection of student information revolves around schools’ and monitoring providers’ data retention and deletion practices. Data collection and retention will vary by monitoring system, and in some cases by type of data collected (e.g. students’ web browsing history, email messages, drive files, etc.). One system, for example, monitors student emails by sending a copy of each email to the monitoring system and analyzing it for indicators of self-harm or other content that the system flags. If content is flagged, the student’s email is saved and the monitoring system sends an alert to school administrators. If nothing is flagged, the copy of the email message is discarded.63

School leaders and monitoring companies should specify the period of time for which student information is retained in the system. School district leaders should consult with their state archives or records officer to determine the retention schedule for any data collected on students. Before publishing a retention schedule, school districts should determine whether any information collected through monitoring would be considered sensitive. Sensitive information, meaning any information that could adversely impact a student’s educational or employment prospects, or could jeopardize a student’s privacy or well-being by being shared, should be deleted as soon as legally allowable.

School districts should publish a retention schedule as part of their transparent communication about policies around the use of monitoring technology and should include information on how information will be destroyed once it is no longer needed. For example, in 2019, Montgomery Public Schools, Maryland, became the first district in the country to publicize a policy to annually delete student information from certain systems, such as internet search histories accumulated through digital vendors, including from the district’s internet content filtering and classroom management provider.64 This plan provides a strong example of appropriately limiting data retention and can serve as a model of effective student data retention policies for other school districts.

Increased data collection and sharing without clear justification frequently overwhelms administrators with information, undermines effective learning environments, casts suspicion on already marginalized students, tends to punish or criminalize students’ medical struggles or disabilities, increases inequities, and can fail to promptly identify individuals who may be at true risk of self-harm. To mitigate these drawbacks, schools should develop clear guidelines about the kinds of material that systems should flag, tailor systems narrowly to respond to actual risks, and think critically about how they address identified concerns.

What harms, such as stigma or discrimination, may stem from sharing of students’ information or flagged status?

Using self-harm monitoring systems raises potential risks of stigma or discrimination. Biases embedded in public perception and media lead to exaggerated fears that students experiencing mental health challenges are prone to violent acts,65 even though most people with mental health needs have no propensity for violence.66 As a result of such biases, school staff may treat flagged students differently from their peers or subject them to additional scrutiny. The common but false assumption that flagged students may be violent can increase harmful stigmas toward the students who need support and can lead them, especially systematically neglected students, to experience disproportionate rates of discipline.67

For example, in 2018, Florida passed a law68 requiring schools to collect information from students at registration about past mental health referrals, while the state’s school safety commission proposed that “students with IEPs [Individualized Education Programs] that involve severe behavioral issues” should be referred to threat assessment teams,69 which are committees created in the wake of the tragic Parkland school shooting to evaluate whether individual students pose threats of violence to the school community. Policies such as these immediately put students who struggle with mental health on a separate tier of scrutiny and potential disciplinary action due to deeply ingrained societal stigma, without leading to improved support or mental healthcare resources for the students. These policies could also have a chilling effect on disclosure. Parents are likely to worry that if their “children’s mental health history becomes part of their school records, it could be held against them.”70 These concerns could result in a loss of trust and an unwillingness to provide schools and districts with sensitive information. In some cases, parents and students may even be disincentivized from seeking mental health treatment for fear that disclosure will harm their future opportunities.

In some cases, even when students seek help on their own, they may experience negative consequences. In one extreme example, the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law represented a college student who voluntarily admitted himself to a campus hospital after a close friend died by suicide.71 When he checked in, the campus hospital shared his health information with university administrators. The next day, while still in the hospital, the student received a letter from the university charging him with a violation of the disciplinary code, allegedly for endangering himself. The student was suspended from school, barred from entering the campus (including to see his psychiatrist), and threatened with arrest if he returned to his dormitory. While his father and friends removed his belongings from his dorm room, he was forced to sit in a car with a university official.

Students who may be considering self-harm or who are struggling with their mental health can be disincentivized from seeking help if they fear that all help sought is monitored.

Situations like these demonstrate the potential harms of invasive or disciplinary school responses to information about a student struggling with mental health. Stigma is unfortunately real and should not be underestimated. Punitive responses contradict the goals of self-harm protection programs because they discourage students from seeking the help they need and engaging openly with mental health counselors or other healthcare providers. While monitoring companies claim their products help schools save lives, students may ultimately experience harm by not searching for resources that could help them out of a fear of being identified by school officials. Students who may be considering self-harm or who are struggling with their mental health can be disincentivized from seeking help if they fear that all help sought is monitored. Moreover, students who are identified as “at-risk” may feel like they have a target on their backs, with their personal struggles facing scrutiny in school. Students’ opportunities should not be limited, either by mental health challenges or by violations of their privacy.

The risk of students being unfairly treated or experiencing discrimination as a result of a self-harm flag can be particularly high in schools and districts without enough school-employed mental health professionals—for example, school-based counselors, school psychologists, social workers, and nurses—a shortage that unfortunately afflicts most schools.72 For detailed information on the potential discriminatory harms and stigma-related effects that can arise once a student is identified, see Boxes 1 and 2.

Box 1. Monitoring Inflicts Particular Harms on Systemically Marginalized Groups of Students

Beyond understanding the risk of criminalization and potential for referral to law enforcement, school districts should carefully consider the uniquely harmful impacts of monitoring on various systemically marginalized groups of students. Below are some examples of groups of students that may experience unique harms as a result of self-harm monitoring.

Students from low-income backgrounds may not have a personal computer or internet access outside of the school campus or school-issued devices, leaving students without the ability to engage online free from their school’s monitoring system. Students without personal devices face more monitoring and associated harms; educators report that while 71 percent of schools who use monitoring do so on school-issued devices, only 16 percent monitor students’ personal devices.73 Students without personal devices may be especially uncomfortable using school devices to seek support, if they know that these devices are subject to monitoring. These disparate impacts may be especially pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic: while learning remotely, students have limited opportunities to seek more information or professional assistance beyond the internet and school-issued devices because they may have limited access to in-person resources. A survey in 2020 found that 8 percent or 4.4 million households do not have a computer always available. In households where a computer was always available, 60 percent received devices from the child’s school or school district.74 Similarly, students experiencing homelessness are unlikely to have access to personal devices and may heavily rely on school-issued devices, while especially needing to use them to search for non-academic resources or supports. These contextual factors suggest that self-harm monitoring programs require clear and transparent boundaries, protocols, and appropriate privacy protections. Otherwise, such programs risk harming the students they intend to protect.

Almost 5 million students in schools across the country are English Language Learners, comprising 9 percent of all public school students.75 Students who are English Language Learners or multilingual, as well as students with disabilities, may be at especially high risk of false, inequitable flagging and of experiencing harm76 from being flagged by a monitoring system. Students who are English Language Learners may often use or interact with content in languages that school officials or a monitoring company do not understand or may interpret negatively.77 Deeply ingrained biases against students who are English Language Learners can especially influence suspicious and negative interpretations of their writing and activities.78 Similarly, students who are English Language Learners may sometimes lack the proficiency or cultural nuance to express themselves as non-English Learners would and may mistakenly use words or phrases that a monitoring program may flag or school officials may misinterpret as a threat to self. As a result, there is a high risk that intent and meaning may get lost in translation, and these students will end up flagged or penalized for innocuous language that school staff fail to accurately decipher. Language barriers or miscommunications and misunderstandings based on differential language use can also surface when monitoring technology scans the content of some students with disabilities.

In addition, monitoring systems may utilize automatic, computerized translations when scanning student content in non-English languages. These computerized translations are frequently inaccurate and fail to account for idiomatic language use or cultural nuance.79 For example, direct translation of a phrase meaning, “You’re annoying me,” from Korean to English resulted in widespread use of the phrase, “Do you wanna die?” in Korean-American communities.80 These inherent shortcomings of monitoring systems risk disproportionately targeting students who are English Language Learners. For more information on legal protections for students who are English Language Learners, see Legal Implications.

In addition to disproportionate risks of stigmatization and criminalization, students with disabilities may be especially harmed by the ways self-harm monitoring systems analyze student content and writing.  Some students with disabilities may interact with online content or use speech differently than their non-disabled peers and may consequently face risks of disproportionate flagging because of the limitations of these systems in interpreting context. Speech that is a manifestation of a disability may be misinterpreted as a threat to self-harm by the monitoring software or by untrained school staff who are unfamiliar with the intersection of disability and mental health. This misinterpretation often occurs with students who have developmental or learning disabilities.81 School district leaders should be aware that disparate treatment of students with disabilities, including disproportionately and needlessly flagging them due to typical manifestations of their disabilities, can constitute discrimination and invite potential legal challenges under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). For more information on legal anti-discrimination protections for students with disabilities, please see Legal Implications.

Some students with disabilities may interact with online content or use speech differently than their non-disabled peers and may consequently face risks of disproportionate flagging because of the limitations of these systems in interpreting context. Speech that is a manifestation of a disability may be misinterpreted as a threat to self-harm by the monitoring software or by untrained school staff who are unfamiliar with the intersection of disability and mental health. This misinterpretation often occurs with students who have developmental or learning disabilities.81 School district leaders should be aware that disparate treatment of students with disabilities, including disproportionately and needlessly flagging them due to typical manifestations of their disabilities, can constitute discrimination and invite potential legal challenges under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). For more information on legal anti-discrimination protections for students with disabilities, please see Legal Implications.

In addition to harms stemming from sharing student information with law enforcement and referring mental health-related issues to law enforcement, students of color may disproportionately experience other harms from self-harm monitoring.

For example, natural language processing algorithms, which are used by monitoring systems, have been shown to analyze and interpret Black dialects of English used online less accurately than writing by white individuals online.82 Likewise, research at MIT shows many common automated tools that scan online content using natural language processing disproportionately flag writing from Black users.83 These examples demonstrate the technological shortcomings, and inequities, inherent in accurately monitoring online content. Such technological inaccuracies lead to racial disparities in students mistakenly flagged by monitoring systems and can cause students of color to disproportionately experience the harms related to mismanaged and privacy-violative monitoring.

Additionally, low-income youth of color and other vulnerable young people may have a very different relationship with school-based and medical-based systems of formal mental healthcare. These student populations may often look to community-based resources and peer social networks as their preferred sources of care and wellness.84 While many monitoring technologies proceed from the assumption that school-based systems of care are best positioned to support young people, that may not be the case for many youth. For many students, state-based systems of mental health screenings and services can trigger harmful episodes where they, or their caregivers, have had to deal with the child welfare system, criminal legal system, juvenile justice system, etc.85 School districts should keep the different needs and preferences of various student groups in mind and recognize that a one-size-fits-all approach to responding to student self harm will not equally benefit all students.

Another important consideration is the effect of high-surveillance schools86 on the academic outcomes and well-being87 of Black students and other structurally disadvantaged racial groups. These students may experience monitoring more as a form of surveillance and control of student behavior than as a mental health support tool, due to the greater prevalence of schools with harsh security and zero-tolerance policies in communities of color.88 In these cases, implementing a monitoring system can add to an atmosphere of surveillance and criminalization, thereby compromising students’ sense of comfort and support in their school environment. Research from John Hopkins University and Washington University shows that high surveillance schools can lead to lower test scores and graduation rates for Black students, as well as greater disciplinary disparities.89

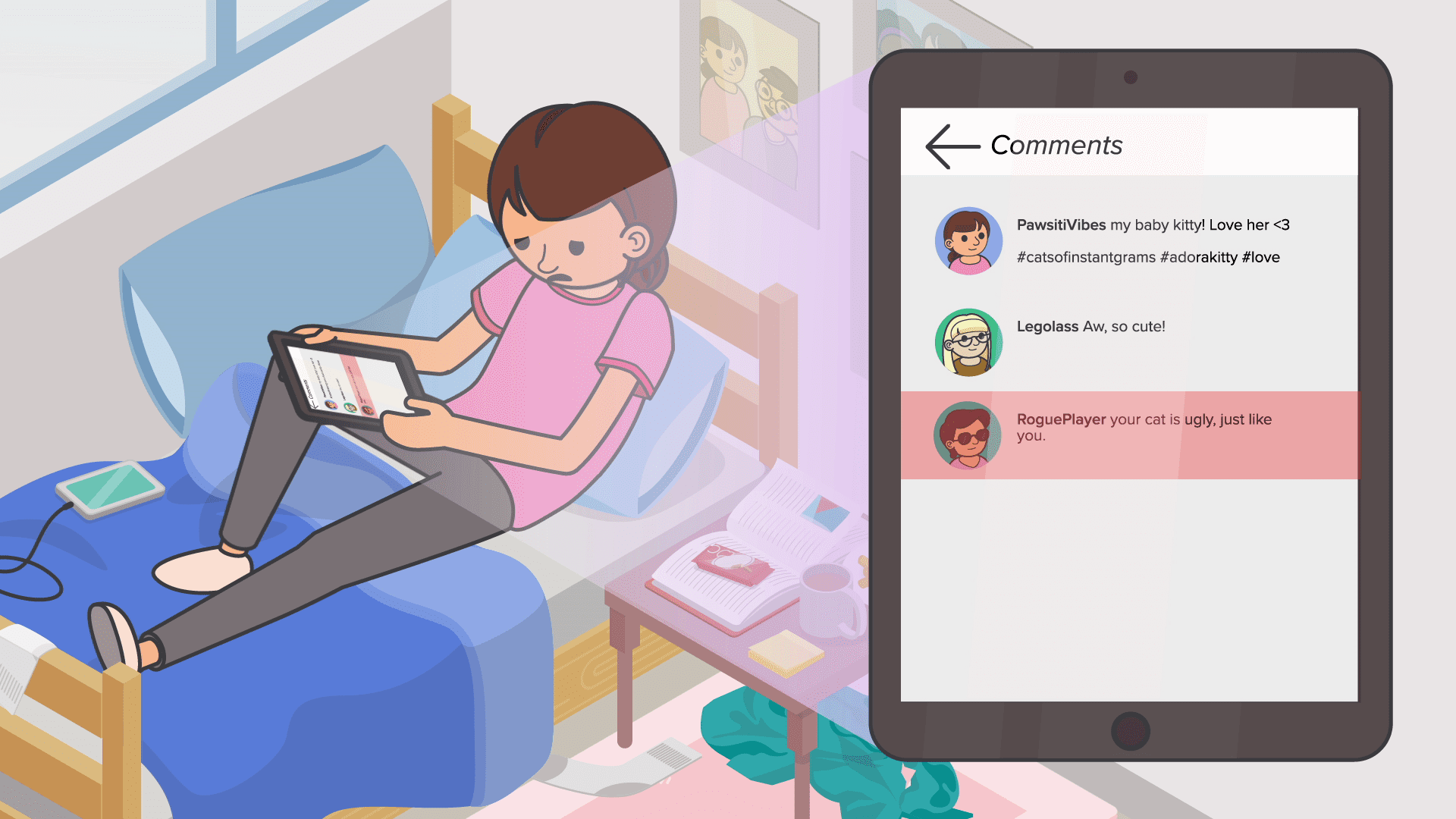

Besides facing the risks of discipline and criminalization described in Box 2, LGBTQ students face unique additional harms from having their digital activities monitored. These unique harms can be exacerbated depending on students’ school and home environments.

Research shows that LGBTQ students who experience victimization or bullying in school face detrimental psychological outcomes, such as higher instances of depression, low self-esteem, increased isolation, and increased suicidal ideation, compared to non-LGBTQ peers.90 The American Psychological Association has reported91 that 64 percent of LGBTQ students feel unsafe in schools because of prejudice and harassment. Sixty percent of these students did not report these incidents to school officials due to fear the situation would be made worse or that the school would take no action to help them. Self-harm monitoring technologies that flag incidents of harassment and prejudice may result in these very fears for LGBTQ students, particularly in unsupportive school environments or without thoughtful protocols for handling flags.

LGBTQ students have a unique interest in controlling who has information about their sexual orientation and gender identity to prevent incidents of harassment, particularly in situations of unsafe home or school environments.

Nonprofit suicide-prevention organization The Trevor Project reports that about 50 percent of LGBTQ youth selectively and carefully decide which family members and teachers and in which contexts they disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity.92 In a national survey conducted by The Trevor Project, less than half of LGBTQ youth had disclosed their identity to an adult at school.93 Research has also found that LGBTQ youth are more likely than their peers to seek identity-related resources and help online.94 Monitoring systems may discourage youth from seeking LGBTQ-affirming resources online if they fear surveillance, repercussions, or reporting or being outed to school staff, other students, or even their parents through the monitoring program.

This ability to decide when and how to come out is a critical right that supports mental well-being, particularly when students are in situations where they may feel unsafe or unsupported. This includes school environments where students do not feel confident that their school leaders would support their identities if they were to report bullying or harassment. Consequently, exposing LGBTQ students as a result of monitoring, even with the good intention to help them, can in fact undermine their mental health and safety by damaging this important protective strategy.

School leaders concerned about the mental health of LGBTQ youth should work to create actively affirming and supportive school climates that respect students’ boundaries and privacy, and to provide resources and information in school related to sexual orientation and gender identity, rather than engage in monitoring that would invasively and forcefully expose these students.

Even if schools do not explicitly regard students experiencing mental health challenges as threats or target them for discipline, monitoring can impact students’ natural exploration, academic freedom, or ability to find online communities and resources that are important for their well-being and mental health.

Research has shown that school surveillance can corrode learning environments by instilling an implicit sense that children are untrustworthy.95

Many organizations have noted that surveillance technologies such as social media monitoring and facial recognition can harm students by stifling their creativity, individual growth, and speech. The sense that “Big Brother” is always watching can destroy the feelings of safety and support that students need to take intellectual and creative risks—to do the hard work of learning and growing. In one study of Texas high school students whose district monitored their social media accounts, students reported that even if they had nothing to hide, they nonetheless found it chilling to be watched.96 A recent national survey found that 80 percent of students who were aware of their schools using monitoring software reported being more careful about what they search online because of knowing that they are being monitored.97

Who has access to the information identified or flagged, and do they have a legitimate health or educational purpose for accessing it?

Because of the harms that can stem from sharing student information, a key privacy issue involves who can access information about which students have been flagged and the content collected by a self-harm monitoring system. Schools should carefully consider which school staff receive information collected through monitoring technologies and what training and communication is being provided to this staff and limit this access to only those who need it to provide specific mental health-related follow-up and support to the students. Schools must also determine if the information may be lawfully disclosed to these individuals.

Coordination among teachers, parents, administrators, and school-employed mental health professionals regarding identified students could help adults spot warning signs and establish comprehensive support plans for the students. Providing increased attention to students’ mental health from qualified individuals may result in better resources and increased care.

Coordination among teachers, parents, administrators, and school-employed mental health professionals regarding identified students could help adults spot warning signs and establish comprehensive support plans for the students. Providing increased attention to students’ mental health from qualified individuals may result in better resources and increased care.

However, simply having information about students’ mental health status, without the skills or capacity to provide specific follow-up or support, could damage teachers’ perceptions of students or negatively affect how the wider school community treats such students. This may be especially true when teachers or school staff receiving this information do not have the training, qualifications, or responsibility for providing mental health-related support to students. Peer-reviewed research demonstrates that teachers do frequently inaccurately identify students as experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety.98 As a result, students may experience the sharing of this information as an invasion of their privacy, resulting in feelings of stigmatization and mistrust.

Simply having information about students’ mental health status, without the skills or capacity to provide specific follow-up or support, could damage teachers’ perceptions of students or negatively affect how the wider school community treats such students.

In addition to considering whether school staff are appropriately equipped to provide mental health-related support to students, schools and districts should ensure that any staff with access to the information identified or flagged are trained on the district’s internal protocol for appropriately handling student information collected through monitoring. Staff must be trained to understand the sensitivity of the information being collected on students, understand appropriate disclosure and use limitations, and be familiar with how and when to appropriately escalate any concerns. They should also be trained on the myriad privacy and equity concerns that arise when students’ online activities are monitored surreptitiously. Finally, staff who may have access to student information collected through monitoring or who may be responsible for following-up with identified students must be trained on the district’s broader mental health policies, including the school’s self-harm prevention and suicide intervention protocols.99

Schools should also consider the potential risks and harms that can result from sharing information collected from monitoring with students’ parents. For example, some monitoring software flags terms related to sexual orientation or gender identity (such as “gay” and “lesbian”) as terms that signify potential bullying.100 If a student is searching for identity-affirming materials and their searches are flagged, what consequences might the student experience if the school shared that information with their parents, to whom the child may not have disclosed these identities? Children in these situations may face serious dangers to their safety and well-being if their home environments are not supportive. More information about this type of harm is presented in Box 1.

Schools and districts should incorporate processes to appropriately ensure that these types of considerations are factored into how, if at all, parents are notified of flags containing sensitive information and what information collected from monitoring is shared with them. These considerations should fall within a broader approach of similar caution that schools must exercise when sharing flagged information with anyone because of the potential negative effects it may have on the identified student. Significant risks arise any time sensitive student information collected through monitoring is shared with any individual who does not directly need access to the information in order to provide mental health-related support.

How is student information shared with third parties, if at all, and are such disclosures permitted by law?

Another key privacy consideration is whether and how schools share student information collected from monitoring programs, including individual students’ flagged status, with third parties, such as law enforcement entities, hospitals, or social services providers.

School districts may be inclined to share a student’s flagged status or mental health information with law enforcement because of biases and misperceptions that conflate mental health problems with violence, or even because of a lack of school-based mental health resources or expertise.101 This conflation of mental health disorders with violence may even be directly promoted by monitoring companies themselves; for example, Gaggle’s homepage prominently states that “70% of students who plotted school attacks showed signs of mental health issues.”102

Sharing student information collected through self-harm monitoring with law enforcement is a particular risk when schools monitor students’ online activity outside of school hours and school administrators are unavailable to respond to afterhours flags. Although sharing the information collected through monitoring software in this manner may stem from good intentions, underlying social inequities cause certain student groups to likely suffer particular harm when schools share their information with third parties or unduly refer them to law enforcement. Monitoring technology itself may not cause the systemic biases that lead particular student groups to experience harm when they are referred to law enforcement. However, school districts must recognize that having a monitoring provider generate law enforcement referrals for self-harm flags can criminalize normal adolescent behavior and subject students to these systemic biases.103 School officials and education leaders must exercise utmost caution to not exacerbate existing systemic injustices for their students through their choice of monitoring provider—undermining the original goal of improving student well-being rather than endanger it.

While harms may also occur from sharing student information with other third parties such as contracted mental health personnel or local psychiatric facilities,104 law enforcement is often the most common third party presence on school campuses, and existing societal inequities make sharing of student information with law enforcement particularly risky for many student groups (see Box 2 discussing vulnerable students and law enforcement).

Does the school district have a plan for providing transparent communication with parents and students, and how have they ensured that the communication plan meets the needs of their community?

Transparency is an essential part of any data initiative. If families and students are unaware of the self-harm monitoring program, schools risk losing their communities’ trust and undermining the goals of their initiative. For example, if a student is flagged when their “mental health problems workbook” includes the word “suicidal,” it may feel like a violation of the confidential relationship between that student and the counselor or therapist who assigned them that workbook.123

If school districts choose to adopt monitoring technology, they must do so transparently, in consultation with experts and community stakeholders, and focus on narrow and straightforward indicators of imminent self-harm. Schools should clearly inform families and students how their online activities are monitored and ensure they know the potential in-school or out-of-school consequences of being flagged. Some monitoring companies have proactively enabled by-default transparency measures—for example, an icon that shows up near the top of a student’s browser when they are being monitored—that can assist schools in providing this transparency.124

School leaders and administrators should consider students and their families as equal partners in selecting, vetting, and developing a self-harm monitoring program prior to implementation.

Schools and districts considering implementing a self-harm monitoring program should ensure families, students, and appropriate school staff understand how the technology works, the internal processes in place to respond to flagged material, which school staff have access to the information collected, and any opportunities students and parents may have for redress in the event of mistaken flags or harmful impacts of being flagged. In particular, when a student is flagged, they and their families deserve access to the information used to make that decision, as well as an opportunity to dispute it. Such proactive communication and transparency will allow students to make more informed decisions about how they use school devices in light of their school’s monitoring policies and will allow students and their parents greater agency in mitigating risks and harms related to being flagged. In fact, some state legislatures have recognized the importance of community engagement around monitoring systems. In California, there is a legal requirement that school districts notify parents and hold a hearing before they can engage in a program to monitor student social media, even if student profiles are public.125

Finally, before implementing a self-harm monitoring program, schools and districts should ensure that their community has had a meaningful opportunity to provide input, raise concerns, and share their perspectives on the program. School leaders and administrators should consider students and their families as equal partners in selecting, vetting, and developing a self-harm monitoring program prior to implementation.

In addition to understanding the privacy and equity risks, school and district leaders should also be aware of the many practical challenges involved in implementing self-harm monitoring. As discussed above, the efficacy of monitoring technologies for reducing self-harm has not been fully evaluated and the technologies have not been substantiated by mental health professionals or clinicians as an effective tool for addressing mental health crises. Beyond questions about the initial accuracy of identifying students in need of support, there are practical challenges to this identification actually leading to the students receiving support, including the widespread lack of qualified mental health personnel in schools. Flagging at-risk students can only be useful if effective follow-up plans and mental health resources are in place for the identified students.

Legal Considerations for School Districts

In addition to understanding privacy and equity impacts, schools should be aware of important legal implications associated with adopting monitoring technologies and collecting student information related to mental health and potential to self-harm. In addition to CIPA (described here), there are several federal laws and protections that may influence how school districts can implement self-harm monitoring programs, manage the student information collected through such programs, and interact with students identified through self-harm monitoring. Additional state laws may apply as well. Schools should be aware of federal and state regulations that may apply to student information collected through student monitoring technologies and weigh these legal implications when deciding whether to adopt monitoring programs. Schools should be sure to consider:

- FERPA and Student Privacy. The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) is the main federal privacy law that applies to student information. In addition to requiring schools to safeguard student data and restricting the parties to whom schools can disclose personal information from student’s education records without parental consent, FERPA affords students and their caregivers or parents certain rights regarding their information. Parents and caregivers have the right to access and correct their children’s education records, and this right transfers to students when they reach the age of 18 or enroll in postsecondary school. Generally, FERPA protections, including limitations on disclosure of student information, apply to information gathered via self-harm monitoring technology. If parents submit a FERPA request for information collected and maintained via self-harm monitoring technology, the law would very likely require schools to provide the parent with the opportunity to inspect that information.

- ADA and Section 504 Disability Discrimination. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is a comprehensive non-discrimination law that provides civil rights protections in all areas of public life to all individuals with disabilities. Likewise, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act provides civil rights protections to all individuals with disabilities in institutions that receive federal funding, which applies to most public schools.133 Both the ADA and Section 504 define disability broadly as a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a record of such an impairment, or being regarded as having such an impairment.134 This means that under these two laws, mental illness is considered a disability, and disability discrimination includes differential treatment arising from the perception of someone having a mental illness, regardless of actual diagnosis.135 This is important information for schools to consider. All children flagged as at risk for self-harm are, by definition, perceived by their school as having a mental health disability that impedes their safety, and are receiving differential treatment accordingly. As a result, school districts should be aware that two different disability-related protections may be triggered when a school flags a student as at risk for self-harm due to potential mental health problems. One is privacy protections that the ADA provides regarding disclosure of a perceived disability/mental health condition; the other is non-discrimination protections for these students under both laws. School districts should carefully consult with their legal counsel around disability protections and examine their follow-up practices to ensure they do not treat students flagged through monitoring in discriminatory ways.136

- Fourth Amendment Considerations. Whether monitoring students’ use of school-issued devices and services at home constitutes an unreasonable search or seizure under the Fourth Amendment remains an open question. The Fourth Amendment implications are also exacerbated when many of the monitoring flags occur outside of school hours. In Minneapolis Public Schools, for example, approximately three quarters of incidents that the district’s monitoring system reported to school officials took place outside of school hours.137 In a recent survey of teachers whose schools use monitoring software, only 25 percent reported that monitoring is limited solely to school hours, and 30 percent reported that their school monitors students all of the time.138 As yet, no Supreme Court jurisprudence has addressed the question of whether monitoring students online while they are at home (whether they use a personal or school-owned device or whether they are connected to their personal or school-provided network) constitutes a Fourth Amendment violation.139 This is especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic; in most cases, students are engaging in their virtual classrooms from the privacy of their homes. Schools and districts should keep in mind the unique sensitivities that arise when monitoring students while they are off campus or learning from home.

- Title VI. Schools should be aware that monitoring students’ online behavior could possibly implicate Title VI considerations. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any program or activity that receives Federal funds or other Federal financial assistance, which includes all public schools.140 The use of these protected characteristics or close proxies of these protected characteristics (such as English Language Learner status) in monitoring or profile-building could thus be a trigger for potential anti-discrimination concerns, particularly if students who are racial or ethnic minorities are disproportionately flagged by school’s monitoring systems or receive disparate treatment as a result.

- Other Legal Protections for English Language Learners. Several laws protect the rights of English Language Learners. The Equal Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA) of 1974 prohibits discrimination against students. It also requires school districts and states’ departments of education to take action to ensure equal participation for everyone, including removing language barriers for ELL students. Additionally, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015 authorizes the U.S. Department of Education to award grants to state education departments, which may issue them as subgrants to K–12 school districts. The subgrants are intended to go toward improving ELL students’ instruction and abilities to meet state academic content and achievement standards. By accepting these federal funds, districts are required to provide language accommodations to non-English-speaking families. The Supreme Court case of Plyler v. Doe also provides protections and rights for students who are English Language Learners in schools.141