The theme for this year’s Safer Internet Day focuses on what companies and institutions can do to improve children’s safety online, represented by the slogan “Together for a Better Internet.” “Together” suggests we all have a role to play. “Better” can mean many things, including the need to include values we believe are important. When the internet was first developed, its primary purpose was to maximize and democratize information sharing. Values like privacy, security, and children’s safety were not prioritized, and we know that if software designers do not include key values in their systems, the systems will not magically reflect those values. For too long, the responsibility of maintaining children’s safety has fallen primarily on parents and the children themselves. By focusing on how we all have a role to play, this year’s Safer Internet Day provides an opportunity to reflect on positive practices for protecting children’s privacy and also areas for improvement.

In a December 2019 article for the Brookings Institution titled “Companies, Not People, Should Bear the Burden of Protecting Data,” authors David Medina and Gayatri Murthy offer a compelling metaphor regarding how we should distribute the burden of ensuring a safer internet: “When we go into a restaurant, we do not check the kitchen to make sure hygiene standards are being met.” Likewise, ensuring children’s safety online should not fall solely on the parents. Particularly in school settings, it should not be the parents’ job to ensure that the schools’ use of educational technologies results in appropriate collection and sharing of students’ data. Parents should be able to trust that schools have structures to safeguard students’ data privacy, just as we trust the kitchen is clean when we go to a restaurant.

There is much that schools can do to keep their metaphorical kitchens clean when it comes to student data. To help educate schools on what they can do, today the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF) released an animated Student Privacy 101 video series. The first video in the series provides background on why student privacy matters. The series then addresses three key areas of student privacy: legal compliance, mitigating risks, and transparency.

Legal Compliance. The legal framework for education privacy is, in many ways, like a restaurant where customers do not have to check the kitchen, but processes exist so that they can, if needed. For example, under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), addressed in the next video in the series, the general rule is that schools may share student data only after they have obtained written parental consent. There are several common-sense exceptions to this rule, however. For example, schools may designate individuals as school officials when they have a legitimate educational interest in the student data. In practice, this means that if an individual performing work in the school or outsourced by the school needs the information to do their job, then they can access the information. Without exceptions like these, schools would be like restaurants where the waiter must constantly get customers’ permission before the chef can do anything.

Mitigating Risks. Legal compliance alone cannot address some risks to the protection of students’ data, however. For this reason, the next video in the series addresses other privacy risks and offers suggestions about other measures that schools can take to mitigate them. Some of these suggestions include instituting a data governance plan, adopting a cybersecurity framework, training educators on privacy, and developing a contract review process.

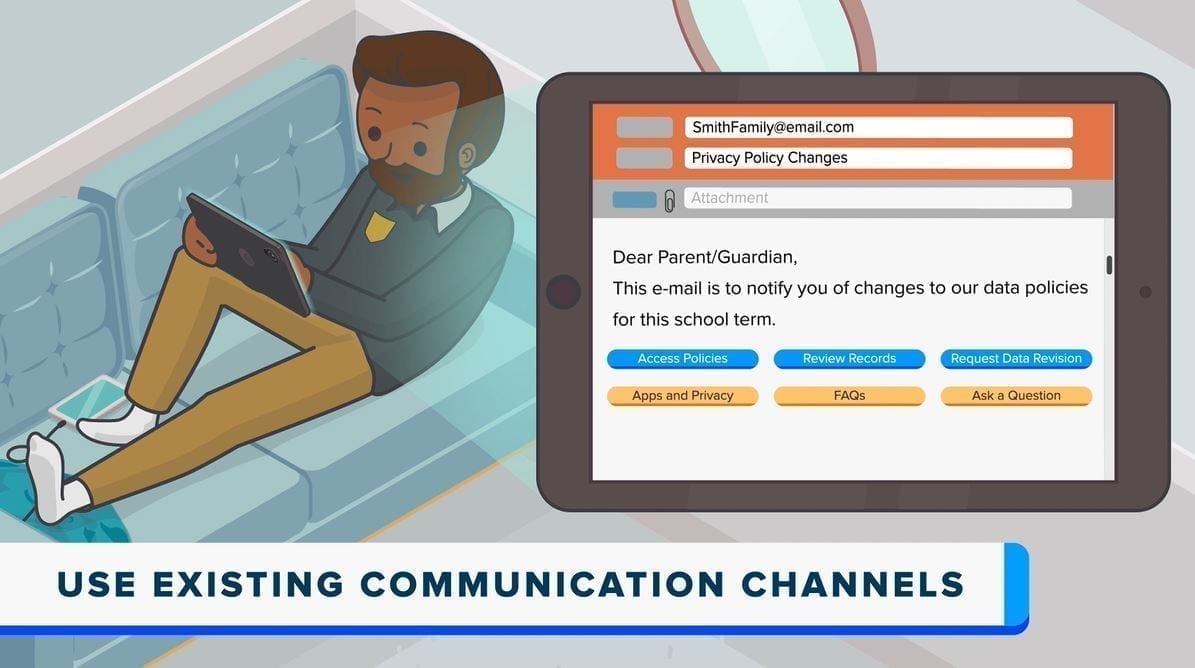

Being Transparent. The last video addresses transparency. This is important because even when schools are legally compliant and address common privacy risks, if parents do not know about it, they may still be concerned about the schools’ policies and practices. As Deborah Stone notes in her book Policy Paradox, parents can be concerned for their children’s safety even when they’re safely tucked in bed. Security is as much a state of mind as it is a physical measure. Schools can be more proactive in sharing their policies and procedures. They can also publicly post whom they share student data with, such as listing on their website all of the educational websites used in the district. They can also take advantage of current methods for communicating with parents, such as by email or during parent-teacher conferences, to highlight privacy initiatives.

Student data privacy practices in the U.S. provide a strong starting point for how institutions can play a positive role in safeguarding children’s data. This video series provides a brief overview of how schools can get started in developing a culture of data privacy. The Future of Privacy Program has other resources that schools can use to improve or establish student privacy programs. In 2019, FPF released the first two parts of a series on practical steps schools can take to begin applying FERPA, specifically, to ensure that parents can inspect and review education records and seek to amend records. The organization also published an article on steps schools can take to build a culture of privacy.

For policymakers seeking to draft legislation to improve student privacy, FPF also released the Policymakers Guide to Student Data Privacy. More resources will be available throughout 2020, so be sure to return to studentprivacycompass.org/, the education privacy resource center.

David Sallay is the student data privacy auditor at the Utah State Board of Education and a contractor for the Future of Privacy Forum. In both of these roles, he is involved in developing training materials, videos, blogs, and other guidance resources for compliance with educational privacy laws.

Dr. Monica Bulger is a Senior Fellow at the Future of Privacy Forum where she works with state and local partners to develop and curate student privacy training resources for K-12 schools. At FPF, Dr. Bulger is conducting national interviews of families, school staff, and state and federal privacy officers to understand the trade-offs of student data use. She is an international child rights researcher focusing on privacy and edtech.