In this series, Privacy and Pandemics, the Future of Privacy Forum explores the challenges posed by the COVID-19 crisis to existing ethical, privacy, and data protection frameworks, and will seek to provide information and guidance to companies and researchers interested in responsible data sharing to support public health response. Access all student privacy and COVID-19 resources here.

School administrators are facing tough privacy questions as COVID-19 continues to spread across the world. Administrators in both preK-12 and higher education are grappling with how to inform communities and public health officials of infections that may emerge among students, how to respond to those cases, and how to maintain students’ privacy during communications.

Today, the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF) and AASA: The School Superintendents Association, released a new white paper, available below and for download, that offers guidance to help K-12 and higher education administrators and educators protect student privacy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This resource is meant to supplement the recently published guidance on how the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) applies to schools in the context of COVID-19 from the US Department of Education (USED).

Student health information is typically protected by FERPA, not the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Consent is usually required before disclosing personal information, but both laws have exceptions when disclosures are made to protect the health or safety of others in an emergency.

The white paper reviews how FERPA and HIPAA govern the disclosure of students’ health information held by schools, and provides answers to the following Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) with examples illustrating how FERPA applies in the context of COVID-19:

- If a student has COVID-19, what information from education records can the school share with the community?

- If the school suspects that a student has COVID-19, what information can the school share with its community?

- If a school suspects that a student may have COVID-19, can school officials contact the student’s primary care physician?

- If a student has COVID-19 and the school’s health records are covered by HIPAA rather than FERPA, what information may the school disclose to its community?

- What if the school receives a voluntary request from a local, state, or federal agency for student records to assist the agency in responding to the COVID-19 outbreak?

- What should a school do if it receives a request under a mandatory reporting law to share student health records with a public health agency?

- Do interagency agreements with other state or local agencies allow schools to disclose education records without obtaining consent?

For clarity, the paper uses the term “school” to refer to any education agency or institution.

How FERPA and HIPAA Apply to Student Records in General

Most student health records held by public schools are subject to FERPA because “the HIPAA privacy rule expressly excludes information considered ‘education records’ under FERPA from HIPAA’s requirements. In short, when FERPA applies, HIPAA does not.” A few exceptions exist, however, and we discuss those below.

FERPA protects personally identifiable information (PII) in students’ education records maintained by an educational agency or institution. Students’ health records maintained by a school—regardless of whether health care is provided to students on-campus or off-site—are considered part of students’ education records and therefore are subject to FERPA. Schools can disclose FERPA-protected information only after obtaining consent from either a parent or the eligible student unless an exception to FERPA’s general consent rule applies. In the case of COVID-19, the most applicable exception to consent is FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception.

According to FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception, if a school determines that there is an articulable and significant threat to the health or safety of a student or other individuals and that someone needs PII from education records to protect the student’s or other individuals’ health or safety, the school may disclose that information to the people who need to know it without first gaining the student’s or parent’s consent. The school is responsible for determining whether to disclose PII on a case-by-case basis by considering all of the circumstances related to the threat. Before disclosing PII, administrators should ask whether that disclosure is necessary and, if so, should disclose the minimum amount of information required to address the issue at hand. We discuss FERPA’s health or safety emergency provision in the context of COVID-19 further below.

In most cases, student health records maintained by a public school are education records subject to FERPA’s consent requirement. However, USED has stated that if a school’s health services are “funded, administered and operated by or on behalf of public or private health, social services, or other non-educational agency or individual,” then that school’s health records are protected by HIPAA, not FERPA. HIPAA prohibits the disclosure of protected health information (PHI) without consent and requires entities subject to the law to establish appropriate privacy protections to protect PHI from unauthorized disclosure. For example, USED has clarified that if a school’s “health care provider . . . delivers health services and engages in covered transactions, such as billing Medicaid for Medicaid-covered services in the school setting,” the resulting records are protected by HIPAA, not FERPA. Like FERPA, HIPAA has an emergency provision allowing the disclosure of protected health information in certain cases. See the FAQs below for further details.

How FERPA and HIPAA Apply to Student Records During the COVID-19 Pandemic

To illustrate how schools can share information about students while protecting their privacy during a public health emergency, we offer the following FAQs with examples that expand on USED’s recent guidance.

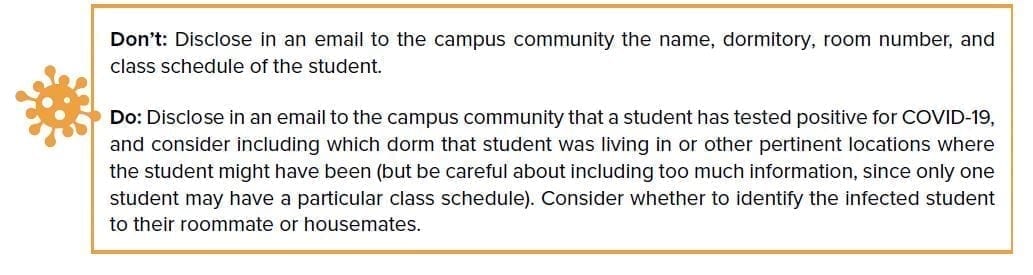

1. If a student has COVID-19, what information from education records can the school share with the community?

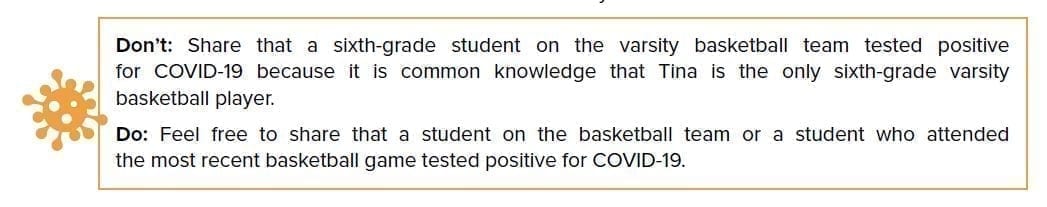

FERPA does not apply when schools disclose that a student may have COVID-19 as long as the school does not directly or indirectly identify that student. Most of the time, in order to receive sufficient notification of risks to their children, parents do not need to know which student was or may be infected, even if they would like to know. For example, let’s assume that Tina, the only sixth-grade student on the varsity basketball team, is diagnosed with COVID-19. Administrators should ensure that any messages to the community do not identify Tina directly or indirectly:

However, the school may determine that certain students who had close contact with Tina when she was potentially contagious should be notified so they can choose to self-quarantine. The school could either obtain Tina’s parents’ consent to release that information or rely on FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception to make a more specific disclosure to at-risk individuals. The health or safety emergency exception applies if the school determines that an articulable and significant threat to the health or safety of a student or other individuals exists and that someone needs PII from education records to protect the student’s or other individuals’ health or safety. Consider these criteria and the actions the school might take in Tina’s case:

- Articulable and significant threat of a health or safety emergency: “Articulable and significant threat” means that the school should be “able to explain, based on all the information available at the time, what the threat is and why it is significant.” USED generally defers to schools on whether something is an articulable and significant threat of an emergency. In the FERPA and COVID-19 guidance, USED states that “[i]f local public health authorities determine that a public health emergency, such as COVID-19, is a significant threat to students or other individuals in the community, an educational agency or institution in that community may determine that an emergency exists as well.” The 2009 FERPA and H1N1 guidance from USED also noted that an emergency could include “sharing information when necessary during the early stages of a pandemic,” and that the “emergency” can last “so long as there is a current outbreak of H1N1 in the particular school or district.”

- The disclosure is necessary to protect the health or safety of the student or other individuals: This language allows the school to decide, as noted above, that Tina’s teacher, classmates and their parents, or students with whom Tina spent significant time need to know that Tina has COVID-19 in order to protect their health.

- Only disclose the minimum amount of information required to address the issue at hand: However, the school should consider carefully how much information it should disclose; would it be sufficient, for example, to just say that someone in Tina’s class has COVID-19, without identifying Tina as the infected student to her classmates? As noted above, as long as the notification does not directly or indirectly identify Tina, FERPA would not apply. If the school does believe they need to identify Tina, they should make sure they provide the minimum information needed—that she has COVID-19 and perhaps a window of time when she may have been infectious, if known—and not additional information such as her health history.

- School officials should be sure to document when they release PII under this exception: The health or safety emergency exception requires the school to list the following information in Tina’s record: the articulable and significant threat that formed the basis for the disclosure and the parties who received the information.

As Tina’s example suggests, administrators should be aware that disclosures made under FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception are not all or nothing. They do not require communicating to everyone or no one. If administrators know that a student is exhibiting symptoms of COVID-19 but hasn’t yet been diagnosed, they could choose to tell only immunocompromised or at-risk students and faculty that a student may have the virus, before communicating with the larger school community. Schools can also combine communication approaches, for example by identifying Tina as necessary to her classmates and their parents but sharing only de-identified information, such as “a sixth-grade student likely has contracted COVID-19,” with the broader school community.

As Tina’s example suggests, administrators should be aware that disclosures made under FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception are not all or nothing. They do not require communicating to everyone or no one. If administrators know that a student is exhibiting symptoms of COVID-19 but hasn’t yet been diagnosed, they could choose to tell only immunocompromised or at-risk students and faculty that a student may have the virus, before communicating with the larger school community. Schools can also combine communication approaches, for example by identifying Tina as necessary to her classmates and their parents but sharing only de-identified information, such as “a sixth-grade student likely has contracted COVID-19,” with the broader school community.

2. If the school suspects that a student has COVID-19, what information can the school share with its community?

School administrators may wish to proactively warn parents and students that COVID-19 may be in the school community to facilitate prevention efforts and ensure that people have the information necessary to address a potential outbreak. Given COVID-19’s high degree of infectiousness, it may be wise for schools to err on the side of caution and notify the entire school when suspected but unconfirmed cases exist. However, it may not be necessary to identify the symptomatic individual. FERPA does not cover “personal observations,” as long as knowledge was “not obtained through the staff member’s official role in making a determination maintained in an education record about the student.” Therefore, it is possible that a teacher who notices that a student looks sick could disclose that information publicly without violating FERPA, but the school nurse who then examines that student and documents observations in that student’s health file could not disclose the observations. School administrators and educators should consider potential harms that could occur if they identify a student, and should use alternative approaches to effectively advocate precautionary measures.

It’s also important to note that FERPA does not cover teachers. If a teacher has COVID-19, a school may share that information without violating FERPA; however, state laws regarding employee confidentiality might apply. One employment law expert advised (page 22) calling the state public health authority and communicating whatever disclosures they advise to the school community.

3. If a school suspects that a student may have COVID-19, can school officials contact the student’s primary care physician?

If a school cannot reach a student or their parents and suspects that student might have COVID-19, they may want to reach out to the student’s primary care physician to ask if the physician can confirm that the student has COVID-19 so the school can notify the community.  This is allowable under FERPA if school officials follow the FERPA requirements that would allow them to disclose that the student is suspected to have COVID-19 to the student’s physician. The school could obtain the parent’s or eligible student’s consent to contact the physician; use FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception as described above; or contact the physician without needing to comply with FERPA if the suspicion results from a personal observation as defined in question 2.

This is allowable under FERPA if school officials follow the FERPA requirements that would allow them to disclose that the student is suspected to have COVID-19 to the student’s physician. The school could obtain the parent’s or eligible student’s consent to contact the physician; use FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception as described above; or contact the physician without needing to comply with FERPA if the suspicion results from a personal observation as defined in question 2.

However, HIPAA may not allow the physician to disclose any information back to the school. Health records outside of the education context are protected by HIPAA rather than FERPA. Like FERPA, HIPAA contains an emergency exception that allows health care providers to disclose protected health information without patient authorization “as necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of the individual, another person, or the public.” A suspected case of COVID-19 indicates that public health and the health of others may be at risk, but that determination is left to the HIPAA-covered entity, which is the health care provider, not the school administrator. If a provider identifies the risk, they would be permitted to disclose the minimum information necessary to the school. However, if a school suspects a positive case, administrators could recommend that the parent take their child to get tested.

4. If a student has COVID-19 and the school’s health records are covered by HIPAA rather than FERPA, what information may the school disclose to its community?

As noted above, the HIPAA privacy rule expressly excludes information covered by FERPA; therefore, it is rare that HIPAA would come into play for schools. However, if the records are covered by HIPAA, that law also includes an emergency exemption allowing covered entities to disclose protected health information without patient authorization. COVID-19 presents a risk to public health and the health of others on campus, indicating a sufficient basis for the disclosure. However, like FERPA, HIPAA requires covered entities to disclose the “minimum information necessary to prevent or control the spread of the disease or otherwise carry out public health interventions or investigations.”

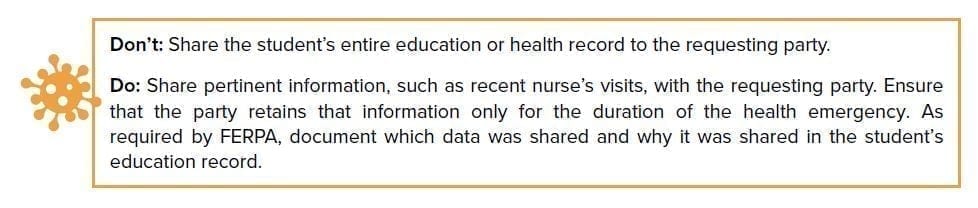

5. What if a school receives a voluntary request from a local, state, or federal agency for student records to assist the agency in responding to the COVID-19 outbreak?

FERPA does not prohibit disclosure of aggregated or properly de-identified information, so administrators may freely share that type of information to help agencies respond to the pandemic. However, FERPA has a specific de-identification standard: schools must assess whether a “reasonable person in the school community, who does not have personal knowledge of the relevant circumstances, [could] identify the student with reasonable certainty” based on both the information the school discloses at that time and other information that community members could combine with the information disclosed. For example, if an agency requests information about student visits to the school nurse due to students’ coughing or fevers (symptoms of the virus) during the months of January and February, follow these guidelines:

Likewise, schools can share information without consent about school absentee rates as long as they provide this information in aggregated or de-identified form.

For more information about de-identification, see USED’s guidance on data de-identification and disclosure avoidance. A school could elect to share PII from student records with a public health agency if the school decides that a health or safety emergency exists and the disclosure is necessary to protect students’ health or safety. As discussed in question 1, any disclosure made to an appropriate party under this exception must be limited to the duration of the identified emergency and be documented in the student’s education record. Moreover, before administrators share any information—because FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception requires school administrators to determine whether an emergency exists and whether circumstances warrant sharing students’ information—they should first carefully consider which information is necessary for the request, even if an exception to FERPA’s consent requirement applies to the circumstances.

6. What should a school do if it receives a request under a mandatory reporting law to share student health records with a public health agency?

Some states have mandatory reporting laws that require schools to report communicable diseases to public health agencies.  Depending on the disease, the information that must be reported could be either PII or de-identified or aggregated information. As a reminder, de-identified or aggregated data reporting is not covered by FERPA, and can therefore be shared at any time. USED previously provided FERPA guidance on disclosing PII based on a New Mexico communicable disease reporting law. Since New Mexico law specified which communicable diseases constituted an emergency that required immediate reporting of PII, USED found that the law likely aligned with FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception and was not preempted. However, USED noted that FERPA does require schools to perform a case-by-case analysis of whether they could disclose PII before reporting information as New Mexico’s law required. This analysis should include whether there is “an identified communicable disease, [that] presents an imminent danger or threat to students or other members of the community, that the release is narrowly tailored to meet the emergency, and that reports are made to appropriate authorities within the health department.”

Depending on the disease, the information that must be reported could be either PII or de-identified or aggregated information. As a reminder, de-identified or aggregated data reporting is not covered by FERPA, and can therefore be shared at any time. USED previously provided FERPA guidance on disclosing PII based on a New Mexico communicable disease reporting law. Since New Mexico law specified which communicable diseases constituted an emergency that required immediate reporting of PII, USED found that the law likely aligned with FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception and was not preempted. However, USED noted that FERPA does require schools to perform a case-by-case analysis of whether they could disclose PII before reporting information as New Mexico’s law required. This analysis should include whether there is “an identified communicable disease, [that] presents an imminent danger or threat to students or other members of the community, that the release is narrowly tailored to meet the emergency, and that reports are made to appropriate authorities within the health department.”

USED emphasized that sharing PII was not allowed in the case of routine or non-emergency reporting that might be required by state or local policies, such as PII regarding students with cancer. If a school is subject to a state mandatory reporting law regarding pandemics like COVID-19, school officials should determine whether the law’s requirements are aligned with FERPA’s health or safety emergency exception. As discussed above, a COVID-19 outbreak in a district is a reasonable basis to find that there is an emergency, so the school officials just need to determine whether they think the public health agency needs to know that information in order to protect the health or safety of others.

7. Do interagency agreements with other state or local agencies allow schools to disclose education records without obtaining consent?

No. Per previous department guidance, “Interagency agreements do not supersede the consent requirements under FERPA. Although an interagency agreement could be a helpful tool for planning purposes, schools must comply with FERPA’s requirements regarding the disclosure of personally identifiable information from students’ education records.” If consent is not obtained, any nonconsensual disclosure to a state or local agency must meet an exception to FERPA’s consent requirement as described above, such as the health or safety emergency exception.

This resource is for informational purposes only and not for the purpose of providing legal advice. You should contact your attorney to obtain advice with respect to any particular issue or problem.

Recommended Resources

This list will be updated on an ongoing basis with student privacy resources relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- FERPA and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (March 12, 2020), U.S. Department of Education.

- Data Privacy in School Nursing: Navigating the Complex Landscape of Data Privacy Laws (Part I) (2019), The Network for Public Health Law.

- Data Privacy in School Nursing: Navigating the Complex Landscape of Data Privacy Laws (Part II) (January 23, 2020), The Network for Public Health Law.

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and H1N1 (2009), U.S. Department of Education.

- Letter to University of New Mexico re: Applicability of FERPA to Health and Other State Reporting Requirements (2004), U.S. Department of Education.

- Coronavirus Teleconference: Legal Aspects of the Public Health Response, and What Employers Should Be Doing Now (2020), Ropes & Gray.

- HIPAA Privacy and Novel Coronavirus (2020), U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.