The Value of Data

Schools have always held a wide range of data about our children and families: Name, address, names of parents or guardians, date of birth, grades, attendance, disciplinary records, eligibility for lunch programs, special needs and the like are all necessary for basic administration and instruction. Teachers and school officials use this information for lots of reasons, including to assess how well students at a school are progressing, how effective teachers are at teaching, and how well your school performs compared to other schools. State departments of education collect data that is then aggregated (summarized) to help guide policy decisions and plan budgets.

Data Can Help Every Student Excel (Data Quality Campaign)

Schools are also increasingly storing electronic data associated with “connected learning,” where online resources are used for instruction and evaluation. Online tools give students access to vast libraries of resources and allow them to collaborate with classmates or even peers around the world. Some of these online tools also give teachers and parents the ability to access and evaluate student work.

Schools should be able to tell communities and policymakers how they collect, use, and protect student data. To learn more about how data can be used to help students, check out the below resources.

- Why Education Data? FAQs

- What Is Student Data? (Infographic)

- Who Uses Student Data? (Infographic)

- Data Can Help Every Student Excel (Infographic)

Federal Laws

There are three federal laws that focus on student privacy that every policymaker should be aware of: FERPA, COPPA, and PPRA. Read all about them below.

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) requires that schools give parents and students the opportunity to access information in their education records. Students and parents are allowed to review and potentially amend incorrect information within their education record. Procedures should be put in place to simplify this process.

A school may not generally disclose personally identifiable information from an eligible student’s education records to a third party without written consent. There are a number of exceptions to this rule, which are laid out in the Department of Education’s FERPA Exceptions — Summary CHART.

| FERPA Directory Information |

|---|

| Student’s Name |

| Address |

| Telephone listing |

| Email Address |

| Photograph |

| Date & Place of Birth |

| Major/Field of Study |

| Dates of Attendance |

| Grade Level |

| Participation in officially recognized activities & sports |

| Weight & Height of Athletes |

| Degrees, Honors, & Awards Received |

| Most recent educational institution attended |

| Student ID, User ID, or other unique identifier (that cannot be used to access education records without a pin or password) |

- FERPA gives parents and students the right to opt out of having their “directory information” shared.

- FERPA allows schools to share student information among designated “school officials” with “legitimate educational interests.” Schools must define these terms, and inform parents who they consider a “school official” and what is deemed a “legitimate educational interest.” This process allows schools to partner with outside persons or entities to provide educational tools and services.

Aside from the two most common FERPA exceptions listed above, there are a number of other circumstances when prior consent is not required to disclose information about a student. The following are categories of people/organizations that may not need express student consent to gain access to certain information about students.

| Individual/Entity seeking information | Type of information available without consent… | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Of Dependent Post-Secondary Students | Generally – any student information | |

| Of Non-Dependent Post-Secondary Students | (1) Information in connection with the student’s health or safety | ||

| (2) Information related to the student’s violation of the law or the academic institution’s policy governing use or possession of alcohol or controlled substances | |||

| Schools | In which the student intends to enroll | ||

| Financial Aid Offices | Facts relevant to determining a student’s eligibility, amount, or conditions surrounding receiving financial aid | ||

| Authorized Representative of Federal, State, and Local Governments and Educational Authorities | Auditing, evaluating, or enforcing education programs | ||

| Organizations | Data used to conduct studies, predictive tests, administering student aid program, or improving instruction | ||

| Judicial or law enforcement authority | In compliance with an order or subpoena | ||

| Victims | Results of a disciplinary hearing of a crime of violence | ||

| Third Parties | Final results of a disciplinary hearing concerning a student who is an alleged perpetrator of a crime of violence and who was found to have committed a violation of the institution’s rules or policies | ||

| Community Notification Program | Information concerning a student required to register as a sex offender in the State | ||

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA)

The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) guides the protection of data, when companies collect “personally identifiable information” directly from students under the age of 13. The FTC updated its COPPA guidance in April 2014 to clarify that “the school’s ability to consent on behalf of the parent is limited to the educational context – where an operator collects personal information from students for the use and benefit of the school, and for no other commercial purpose…. because the scope of the school’s authority to act on behalf of the parent is limited to the school context.” School consent cannot substitute a parent’s approval “in connection with online behavioral advertising, or building user profiles for commercial purposes not related to the provision of the online service.”

Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment (PPRA)

| PPRA Sensitive Information |

|---|

| Political Affiliations |

| Address |

| Mental & Psychological Problems |

| Email Address |

| Sex behavior & Attitudes |

| Date & Place of Birth |

| Illegal, anti-social, self-incriminating & demeaning behavior |

| Critical Appraisals of other individuals |

| Legally recognized privileged or analogous relationships |

| Participation in officially recognized activities & sports |

| Income |

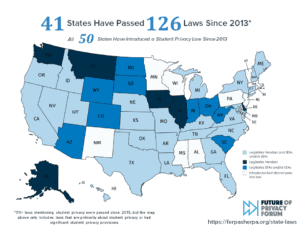

Effective policies enacted at the local, state, and federal levels can curtail the risks accompanying student data collection and ensure that data is used ethically to support learning. Since 2014, state policymakers have built new legal frameworks, passing over 130 laws to protect student privacy. As data breaches and privacy issues continue to capture public attention, it’s up to policymakers to develop thoughtful approaches to student data privacy: legislation, rules, policies, and technical safeguards that protect student data and can adapt to a quickly evolving technological environment.

How is Student Data Used?

Parents, educators, and policymakers all use student data—academic information, assessments, demographics, teacher reporting, and data created by students themselves such as homework or participation in activities—for varying purposes. For example, parents might use student data to support academic growth at home. Educators might use it to inform effective instruction and communicate with parents. Policymakers often rely on aggregate data to allocate resources or craft laws. These uses, in addition to many cutting-edge technologies, rely on student data to support students and develop effective, data-driven approaches to education. However, particularly in the context of education, questions regarding who collects and has access to student data remain constant, especially in light of the recent increase in data breaches across nearly all sectors of business and government. A lack of transparency about both the scope and type of student data use can create distrust among stakeholder groups and can cause misinformation to drive the student privacy conversation. Without appropriate guardrails in place, individual student data can be used for non-educational purposes, such as commercial advertising, immigration matters, and law enforcement. Stakeholders have also raised concerns about edtech vendors that collect, use, retain, and share student data for these non-educational purposes. In response, many states have passed laws prohibiting the use of student data for these purposes, such as building student profiles for advertising.

To learn more about how data can be used to help students, check out the below resources.

- Why Education Data? FAQs

- What Is Student Data? (Infographic)

- Who Uses Student Data? (Infographic)

- Data Can Help Every Student Excel (Infographic)

Which Federal Laws Already Address Student and Child Privacy?

The two main federal laws that focus on student records and children’s data are The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act.

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act(FERPA)

Enacted in 1974, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) guarantees parents access to their children’s education records and restricts the parties to whom schools can disclose students’ education records without consent. Under FERPA, “education records” include records maintained by an educational agency or institution (or a party acting on their behalf) that contain information directly related to an individual student. Because FERPA’s requirements are mandatory for schools that receive funding from the U.S. Department of Education, the law applies in most K–12 schools and in many public and private post-secondary institutions. Regulators enforcing FERPA have the authority to enter into mediation with schools to resolve violations, prohibit schools from working with certain third parties, and withhold all federal funds from education institutions that violate the law. Today, FERPA remains the main federal law governing student privacy in schools. However, while technology has shifted greatly, the statute has not been routinely amended by Congress.

FERPA permits schools to share information contained in a student’s education record under certain circumstances. For example, most edtech companies, such as gradebook systems or classroom learning programs, receive student information under the “school official” exception. The exception says that a school may share education records with a third-party service provider if there is a “legitimate educational interest” in disclosing the information, the third party is performing a service the school would otherwise perform itself, and the third party is under the school’s “direct control.” FERPA is quite strict––but not always clear––about what third parties may do with information they receive under the “school official” exception. Schools must ensure that the third party uses FERPA-protected information only for the educational purpose at hand. For example, third parties cannot create user profiles in order to target students or their parents with advertising, collect information beyond what is necessary to fulfill their agreements, or share information from education records, except with subcontractors who are helping fulfill the third party’s contract. In 2014, the Department of Education released guidance on FERPA requirements regarding student data and online educational services. One issue the guidance addressed was metadata—data that describes other data, such as the author, date created, and size of a particular document—stating that identifiable metadata (e.g., a student’s username in a homework document) falls under FERPA, while metadata stripped of direct and indirect identifiers does not. This sort of information fills in the contours of FERPA, helping to clarify what the department believes federal law covers and what gaps remain.

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA)

The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) governs the information that companies operating websites, games, and mobile applications can collect from children under the age of 13. Applicable to all online products directed toward consumers under 13 and to situations in which companies have “actual knowledge” that a specific user is 12 or younger, COPPA requires companies to have a clear privacy policy, provide direct notice of data collection to parents, obtain verifiable parental consent for collection of any personal information from a child, and allow parents to request deletion of their children’s data. Educators and other school officials such as district administrators are authorized to provide consent on behalf of parents for the use of products in the context of educational programs. In these instances, a company can only collect personal information from students for a specified educational purpose, not for commercial purposes. COPPA is enforced by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and state attorneys general, which have the power to investigate complaints, require violators to change their practices, levy fines, and enter into settlements.

Other Federal Laws of Note

While FERPA and COPPA are the two main federal laws concerned with protecting student data privacy, several other laws have narrower privacy applications.

The Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment (PPRA) regulates student participation in any survey, analysis, or evaluation funded by the U.S. Department of Education. Before a school administers surveys asking for certain personal information, parents must be allowed to review the survey. If a survey asks about sensitive subjects such as political affiliations, anti-social behavior, religious beliefs, or family income, parents must be notified and given the opportunity to opt their children out of participating. PPRA also prohibits the collection of information from students for marketing purposes. One important exception is that PPRA data use restrictions do not apply to the collection, disclosure, or use of students’ personal information for developing, evaluating, or providing educational products or services or to students or educational institutions.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) provides for a “free appropriate public education,” including special education and services, for children with disabilities. The law authorizes grants to states that comply with its requirements. In addition to granting parents access and deletion rights that are similar to those of FERPA, IDEA also establishes a higher standard of confidentiality for the student records it covers, such as a student’s Individual Education Program. While IDEA is not typically central to the student privacy conversation, policymakers should be aware of IDEA’s provisions when they consider specific protections for students with disabilities.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was designed to create standards for electronic health care transactions and to protect the privacy and security of individually identifiable health information. In most cases, HIPAA does not apply to student records since it generally applies only to health information possessed by “covered entities” such as hospitals or physicians. However, the two laws overlap to some degree, as FERPA incorporates the security standard set out in HIPAA. For a detailed examination of how HIPAA impacts student records, see the HIPAA-FERPA guidance in the resources section on page 12.

The Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA) applies to schools and libraries that receive discounts for internet access or internal network connections through the E-rate program, which is administered by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and makes certain communications services and products more affordable. Schools and libraries subject to CIPA are required to create an internet safety policy that includes technological protection measures that block or filter access to obscene online content. CIPA also requires schools to monitor students’ online activities, and how they do so must be referenced in schools’ internet safety policies. Policymakers who wish to address content or internet access restrictions in schools should be aware of CIPA’s carefully balanced approach, which reflects both the intent to protect minors from harmful content and the First Amendment’s protections for access to information and speech online.

Federal Security Standards

In addition to establishing protections for student and child privacy, both FERPA and COPPA require schools and companies to have data security measures in place. The security requirements, which apply regardless of the technology in use, require schools and companies to use “reasonable” steps or methods to provide security. Some states are considering taking an additional step by linking security requirements to the National Institute of Standards in Technology (NIST) cybersecurity framework. Technical assistance is available through NIST, the Department of Education, and other organizations to help companies and districts implement security measures.

State Laws and Legislation

Do you know if the state you are working in has a student privacy law? Just since 2013, over 100 new student privacy laws have passed in almost all states. Most of those laws impose new requirements on districts, states, and school service providers.

What Are Common State-Level Approaches to Regulating Student Data?

States have approached the regulation of student data use in three ways. The first is by regulating schools (LEAs) and state-level education agencies (SEAs). For example, Oklahoma’s 2013 Student Data Accessibility, Transparency, and Accountability Act (Student DATA Act) addressed permissible state-level collection, security, access, and uses of student data. Bills following the Oklahoma model have limited data collection and use and defined how holders of student data can collect, safeguard, use, and grant access to data.

The second approach has been to regulate companies that collect and use student data. For instance, California’s Student Online Personal Information Protection Act (SOPIPA) prevents online service providers from using student data for commercial purposes, while allowing specific beneficial uses such as personalized learning. California supplemented SOPIPA by enacting AB 1584, a law that explicitly allows districts and schools to contract with third parties in order to manage, store, access, and use information in students’ education records. An enforcement provision, AB 375, was also added to give the California Attorney General additional authority to fine companies that violate SOPIPA and AB 1584. This law has become a model for the regulation of edtech vendors’ use of student data. More than 20 states have since adopted similar laws.

The third approach combines the first two models. For instance, to regulate its state longitudinal data system, Georgia chose to follow Oklahoma’s lead in addressing three core issues regarding state education entities: which data is collected, how student data can be used securely and ethically, and who can access student data. Combined with SOPIPA-like regulation of third parties, this approach has allowed innovative uses of student data while establishing meaningful privacy protections for students. Similarly, Utah has taken a modified hybrid approach by regulating districts, the state education agency, and companies. Utah took the additional step of creating and funding a Chief Privacy Officer and three additional privacy staff not only to carry out the law but also to provide training for teachers and administrators and to create resources that help stakeholders ensure compliance.

Since 2015, state legislation has tended to regulate data use rather than collection, and to focus laws on specific privacy topics such as data deletion, data misuse, biometric data, and breach notification. For a closer look at state law trends, see the list of student privacy state laws passed since 2013 on Student Privacy Compass.

Do General Privacy Laws Address Student Data?

Some state-level general privacy laws are written broadly enough to apply in the school context. It is important to be aware of the possible impact of these general privacy laws, as they may cover schools or create unintended consequences regarding education data.

Yes. The California Electronic Communications Privacy Act (CalECPA) prohibits state governmental entities from searching Californians’ phones without consent, a warrant, or during an emergency. This broad prohibition was intended to restrict law enforcement access to citizens’ electronic communications. However, the statutory language unintentionally included school officials such as administrators, effectively changing decades of practice that allowed administrators to search students, under a lower standard imposed by the Supreme Court.

While heightened requirements for searching students’ phones can protect privacy, they have also unintentionally harmed students. In one instance after CalECPA passed, students circulated explicit pictures of a girl around their school. Yet, school administrators were unable to search the students’ phones because they did not have the evidence needed to obtain a warrant. The girl, humiliated, ended up moving to another school district because the law kept officials from stopping the sharing of the images.

In addition to prompting more narrow privacy laws, increased public concern about privacy issues has led to the 2018 passage of the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), a general privacy law that restricts companies’ use of Californians’ data. The implications of CCPA for education in California are not clear, but CCPA and California’s education-specific law, the Student Online Personal Information Protection Act (SOPIPA), differ in some areas, especially regarding edtech vendors. For example, SOPIPA requires education vendors to provide schools with access and deletion rights for student information, but CCPA provides those rights to all consumers whose information is held by a business, which may include edtech vendors. This conflict could allow a student who is still in school to contact an edtech vendor and delete their information, including grades and homework, an outcome that CCPA’s authors likely did not intend or anticipate.

As state legislatures implement general consumer privacy laws, policymakers should be mindful of the interaction between new proposals and existing student privacy rules.

What Are Potential Issues to Consider When Drafting Student Privacy Legislation?

Policymakers at both the state and federal levels have taken up numerous specific issues in student privacy laws. Even well-intentioned actions can result (and have resulted) in unintended consequences. Policymakers should be aware of past laws that have been reconsidered and revised in response to stakeholder feedback.

Vendors and Third-Party Student Data Use

States are increasingly choosing to address third parties’ collection and use of student data, specifically companies that provide services in schools. While SOPIPA-like laws are the most common, some states have imposed indirect requirements on companies by requiring schools or districts to protect the student data they share with vendors. Third parties provide various important services in schools that involve student data and do not typically raise privacy concerns, such as school photography or transcript delivery. Policies that are not carefully crafted may inadvertently impact these and similar services. For example, a prohibition of the collection of “biometric information” could include class and yearbook photos, and a ban on the sale of all student data could include student data in transcripts sent to colleges. Anticipating these types of unintended consequences is vital for creating effective privacy legislation.

Student data can be useful for researchers, for instance to study the efficacy of technology products, to determine whether a new nutrition initiative is effective, or to understand why test scores vary across a district. Research and data are necessary to create evidence-based education policy and to monitor whether policy decisions are effective. FERPA permits the disclosure of student education records to researchers without the need to obtain consent. Leaders who determine which data will be shared with researchers under applicable laws should determine the school or state’s research priorities, communicate those to the broader community, and have a standardized method of interacting with outside researchers.

Transparency

Transparency requirements, including things such as mandatory communication between administrators and parents, can help to address the concerns of parents, students, and others about how data is used. Transparency measures are an important part of building trust among different stakeholders in education. Moreover, school records are often subject to Freedom of Information Act and open government requirements, so clear processes that promote transparency can help schools comply with requests for information.

That said, poorly crafted transparency requirements can be unwieldy and ineffective. A Connecticut law, HB 5469, required local and regional boards of education to electronically notify parents every time they signed a new contract with a vendor. Because districts generally contract with dozens or hundreds of vendors for various services, LEAs were overwhelmed by the number of notices they were required to provide, and parents were flooded with so much information that the intended value of the transparency measure was lost. Once districts shared how the law was working on the ground, the state legislature acted quickly to amend the law, allowing districts to provide a comprehensive notice annually instead of after every contract.

Parental Rights

In many instances, policymakers have chosen to establish rights for parents regarding student data. While this can ensure transparency and create meaningful student protections, it’s not always a perfect solution. In several cases, requiring a parental opt-in for education technology has caused unintended consequences.

For example, in 2014, Louisiana required opt-in parental consent for student data use, effectively precluding some beneficial uses of student data. And because the law carried criminal penalties, teachers and administrators did not want to risk jail time, so they shied away from using student information in any way that could violate the law. As a result, printing news stories about local football teams, yearbook publication, and recommendations for state-funded college were disrupted.

New Hampshire’s 2015 state student privacy law also caused unintended consequences. The law required teachers to get written approval from the school board, parents, and a supervising teacher before they could record video in classes. While the law was intended to protect students from classroom surveillance, it also prevented students with learning disabilities from using video technology to assist them in the classroom. Additionally, the law prevented student teachers in New Hampshire from recording themselves in action—a requirement for certification. The New Hampshire legislature has since carved out an exception allowing classroom recordings for students with disabilities, but student teachers still require approval from the school board, all parents, and the supervisory teacher before they can record themselves.

Data Governance and Security

To create policies on governance and security— processes and systems governing data quality, collection, management, and protection—policymakers should include defined, formal roles for school officials and limits on data access, disclosure, and use. Beyond establishing physical security measures such as limiting who has access to the places where student information is stored, states have also worked to implement software security standards to keep student data safe from potential breaches.

For example, West Virginia enacted its own version of Oklahoma’s Student DATA Act, which includes formal policies defining roles and responsibilities; data access, disclosure, and use; data management and monitoring; and how data is collected, accessed, and used. The law created procedures for compliance, training for all stakeholders, strategies to respond to incidents, and public forums to increase transparency.

Training

For student privacy legislation to be effective, administrators must have the tools and training they need to implement privacy protections. This training often includes basic internet and computer safety, how to safely and effectively use data, which apps and programs are safe to use, and the dangers of unintentional disclosures. Even with strong student privacy laws, schools lacking effective training may struggle to comply with legal requirements. Unfortunately, training mandates are often unfunded, leaving districts with difficult choices about how to provide privacy training without reducing funding in other areas. Utah is currently the only state that requires an annual course for educator relicensure, although many states and districts, large and small, have found ways to build a culture of privacy.

School Safety and Surveillance

In light of many recent, horrific school shootings, officials have considered measures such as surveilling students online in an attempt to keep students safe. While student safety programs are crucial, policies should be carefully considered to ensure they meaningfully increase school safety while minimally impacting students’ privacy. Surveillance can impact students in many ways, such as the feeling of constantly being watched, which can lead to a loss of student autonomy and creativity. Evidence also shows that school surveillance disproportionately affects disadvantaged and minority students. When setting policy, policymakers must employ evidence-based practices to carefully balance actions that meaningfully increase safety with those that infringe upon student privacy. In the wake of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, Florida passed a law, FL 7026, that created a database of information from social media, law enforcement, and social services agencies. Privacy groups have expressed concerns that this large-scale data sharing could be used to inappropriately track and discipline students for non-safety reasons.

Higher Education and Early Education Privacy

Higher education and early education contexts raise related but distinct privacy issues because their institutions and students often have different priorities than those in the K-12 space. Many of the issues highlighted in this guide have different implications in the contexts of higher education or early education. That said, it is possible for laws intended to apply only to K-12 to be drafted in ways that make them apply to higher education and/or early education because the authors were not sufficiently specific. When creating policy, policymakers must be explicit about which institutions are covered.

Which Stakeholders Should Policymakers Consult When Considering Measures to Protect Student Data?

For policymakers, engaging with key stakeholder groups—students and parents; educators; district-, state-, and federal-level education officials; edtech vendors; and other third-party service providers—can be crucial for effectively protecting student privacy. Not only will these groups inform policy positions, they can also be useful for learning about which student data privacy practices are effective on the ground.

Students and their families are central to all student data privacy legislation. In order for students to excel in our nation’s schools, students and parents must understand student data practices and trust that data will not be improperly disclosed. A best practice is for policymakers to engage with parents and students to create legislation that tackles student data privacy and ensures a safe, trusting learning environment.

Educators commonly use student data in the classroom to help their students learn. Recently, some states have implemented 1-to-1 device programs (providing a device to every student), and technological integration is increasingly common in today’s digital world. Engaging with educators to understand how technology is used in the classroom can be an important step in crafting policies, especially to avoid unintended consequences. Further, educators can help to clarify gaps in training, budget, or policy at the school level that policymakers can address.

District, state, and federal education officials are generally responsible for ensuring that student data is properly collected, shared, and protected. These officials often have limited capacity to create and implement complex student data privacy programs, which may lead to ineffective or burdensome data governance programs. Education officials are well situated to identify systemic gaps where legislation is needed, and often have particularly valuable insights about how to create effective protections for student data.

Lastly, as providers of most of the technology used by students in modern classrooms, edtech vendors and service providers, from large companies to small startups, are also a vital part of the student privacy conversation. Vendors are commonly subjected to contractual provisions or legislation that restrict how they can use student data, and therefore can provide a unique perspective on measures that can help students succeed and promote innovation.

Resources for Policymakers

Many resources beyond Student Privacy Compass provide general and targeted information to answer policy-based questions. The following list outlines many of the available sources.

- The U.S. Department of Education’s Privacy Technical Assistance Center is a resource for education stakeholders to learn about data privacy, confidentiality, and security practices related to student-level longitudinal data systems and other uses of student data.

- The National School Boards Association has created guides for school leaders on student data privacy and security and hosts a Cyber Secure Schools initiative designed to help protect the personal information of students and employees.

- CoSN Privacy Toolkit for School Leaders provides school officials with ten essential skills areas, outlining the responsibilities and knowledge needed to be an educational technology leader. CoSN also runs the Trusted Learning Environment (TLE) Seal, the nation’s only data privacy seal for school systems, focused on building a culture of trust and transparency. The Program requires school systems to have implemented high standards for student data privacy protections.

- U.S. Department of Education Guidance, “Protecting Student Privacy While Using Online Educational Services: Requirements and Best Practices,” clarifies FERPA’s requirements regarding student data use in the context of online education services.

- Data Quality Campaign’s 2018 trends publication provides a thorough description of state law trends in student data privacy.

- The National Conference of State Legislatures’ resources include policy questions to consider and legislative examples with links.

- FPF and ConnectSafely’s Educator’s Guide to Student Data Privacy helps educators understand their role in protecting student data and navigating the laws governing student information.

- The Student Privacy Pledge is a list of commitments to which K-12 school service providers agree to in order to safeguard student data privacy regarding the collection, maintenance, and use of students personal information.

- National PTA, FPF, and ConnectSafely created the Parent’s Guide to Student Data Privacy to help parents understand the laws that protect students’ data and rights.

- Data Quality Campaign has created both an infographic and a video outlining the uses of student data.

- Data Quality Campaign provides information on state laws annually and other useful privacy review tools and resources.

- Future Ready Schools, a project of the Alliance for Excellent Education, has a set of resources and a privacy self-assessment designed for districts.

- Department of Education & Department of Health and Human Services, “Joint Guidance on the Applicability of FERPA and HIPAA to Student Records” provides information about the interaction of FERPA and HIPAA in the context of schools and student information.

- American Legislative Exchange Council: Model Language for Student Data Accessibility, Transparency, and Accountability Act

- Education Counsel: Key Elements for Strengthening State Laws and Policies Pertaining to Student Data Use, Privacy, and Security: Guidance for State Policymakers (March 2014) In an effort to assist states with developing policies reflecting the modern era of digitized education data, this guidance draws on federal law, state examples, and best practices and examines key issues and elements for state leaders to consider for protecting privacy and security of personally identifiable education and linked workforce data.

- Electronic Privacy Information Center’s Student Privacy Bill of Rights (March 2014) Khaliah Barnes, director of the Student Privacy Project and administrative law counsel for the non-profit Electronic Privacy Information Center, lays out a Student Privacy Bill of Rights that gives back to students control over information about their lives.

The Latest

Work Smarter Not Harder: How New York Leveraged Existing Education Services Infrastructure to Comply with New Privacy Laws

Mar 20, 2023Bailey Sanchez and Lauren MerkLearn MoreWhat Can States Learn From New York’s Approach to Student Privacy?New Future of Privacy Forum analysis highlights the benefits of New York’s regional, shared-s…

Online Safety Tips for Education Professionals

Nov 4, 2022Nicholas Matera and Chloe AltieriLearn More